Brief Reflections on Intellectual Effort as Private Property and Economic Commodity, Copyright, and The Social Activity Called Art

“’Authorship’ – in the sense we know it today, individual intellectual effort related to the book as an economic commodity – was practically unknown before the advent of print technology. Medieval scholars were indifferent to the precise identity of the “books” they studied. In turn, they rarely signed even what was nearly their own. They were a humble service organization. Procuring tests was often a very tedious and time-consuming task. Many small texts were transmitted into volumes of miscellaneous content, very much like “jottings” in a scrapbook, and, in this transmission, authorship was often lost.

The invention of printing did away with anonymity, fostering ideas of literary fame and the habit of considering intellectual effort as private property. Mechanical multiples of the same text created a public – a reading public. The rising consumer-oriented culture became concerned with labels of authenticity and protection against theft and piracy. The idea of copyright — “the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, and sell the matter and form of a literary or artistic work” — was born.”

–Marshall McLuhan

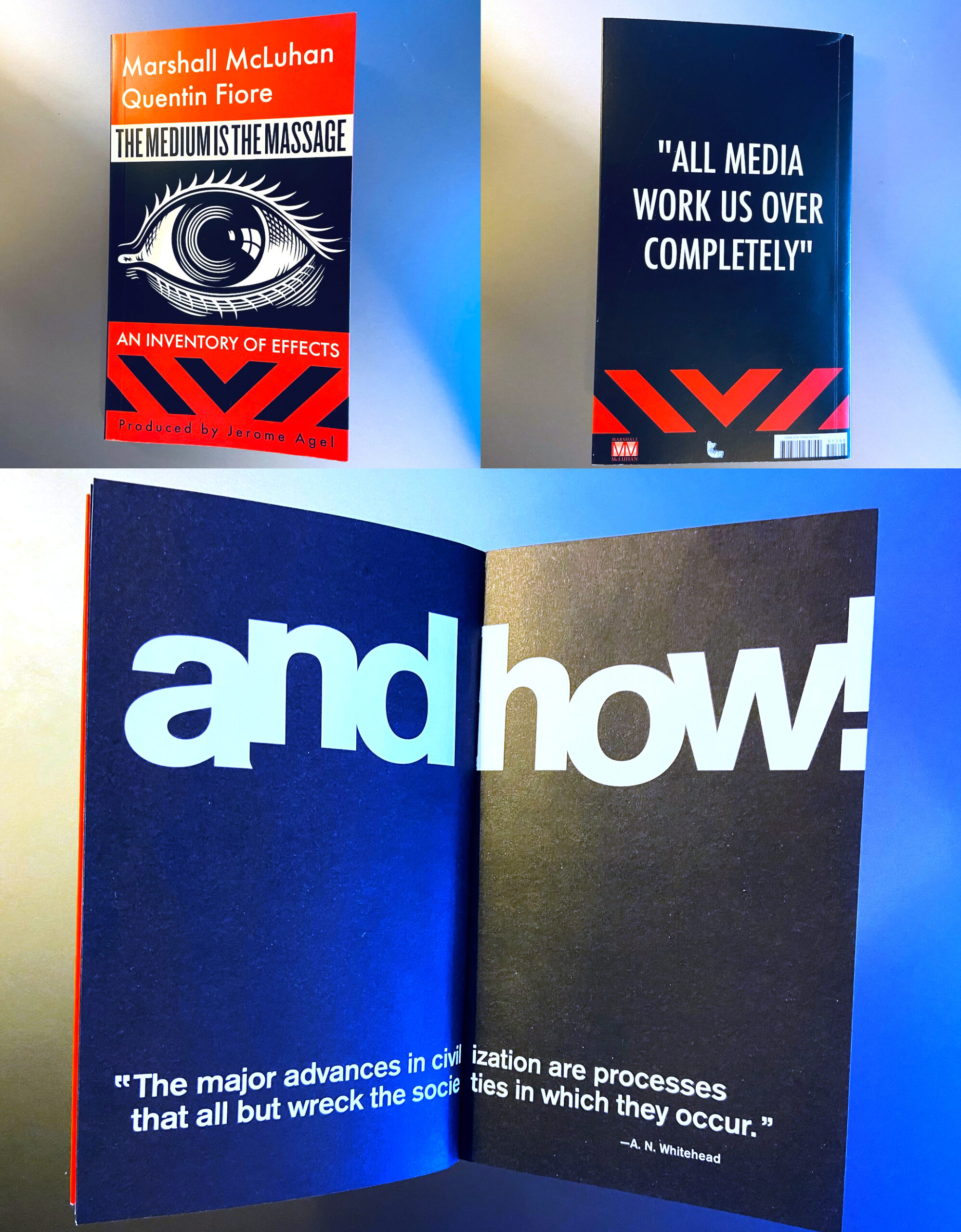

I came across the above passage while skimming through the new copy of Marshal McLuhan’s famous book, The Medium is The Message, that I recently picked up. I’ve read the book before having gone through a big McLuhan phase over 10 years ago. It’s nice to revisit some of his ideas and I recommend the book for more than just McLuhan’s media theory. The version of the book I bought again was designed by Quentin Fiore, a designer and collaborator of McLuhan, whose work I really appreciate. The design and layout of the book is really fun and unique for a book about boring theory, in fact I wish more philosophy and theology books looked like this:

Look at that nice Whitehead quote, WILL YA!

Anyway, upon reading the bit about copyright above I had the thought that McLuhan MUST be channeling French literary theorist, Roland Barthes, who famously declared that writers and/or artists are not geniuses or gods and that, in fact, writers and artists were merely scribes or craftspeople skilled at using a particular linguistic and/or visual code. McLuhan and Barthes may not have been bros but at the very least I suspect they were familiar with each other since they both fancied themselves as literary theorists in some form (I know McLuhan started teaching in English departments anyway…). But the whole idea that Barthes is suggesting here, and which McLuhan seems to be affirming (that art is indeed a social activity), is one that I bet would rustle a lot of people’s feathers, especially artists.

I’ll explain.

As a designer I disabused myself of the notion that my work was my own quite a while ago. I don’t sign my work. I’m a co-creator, a collaborator. NOT a genius or god/God that creates ex nihillo. I fully acknowledge this. Often times I don’t take the photographs I use in the designs I create, and I’ve used lots of illustrations from illustrators way more talented than me in past projects. Similarly, I hardly ever write the copy I use in projects that I work on. We can of course get more granular here if we want to (e.g. the font I’m using to type this right now was not designed/created by me) but all of that to say this: it is because of these sort of reasons, as well as the recognition that designers generally have a “client” who has hired them, that I used to go about analogizing the difference between art and design by describing art as masturbation and design as sex; one discipline is self-centered and the other involves pleasing others. Unfortunately, if we go along with Barthes and McLuhan and admit that art too is a social activity closer to that of craft and design, then I guess I will have to give up my shocking and snarky but noneltheless profoundly hilarious analogy…Oh well

Additionally, McLuhan’s discussion about copyright above brought to mind more good topics which I’ve explored before that deal with art and profit (here and here for instance), topics that are ever relevant today with recent news (and criticism) coming out alleging that Spotify pays “an industry low of under half a cent per stream.” I would not dream to challenge any sort of suggestion put forth that would urge Spotify to pay recording artists more money; Spotify is probably the biggest and most profitable music streaming platform so for that reason alone, absolutely. Shame on them! That said, I stand by what I’ve written before with regard to art and profitability:

If artists wish to be viewed as production workers, who produce a product or commodity, then of course, they deserve to be compensated fairly for their time, materials and labor. No doubt.

However, if artists want to be considered production workers, who function in a neo-liberal market economy like the rest of us, they must accept that the value of art is simply the same as market value and must succumb to the rule of supply and demand. Therefore, if small time indie artists want to make a living on their art, it’s in their best interest to produce a “product” that is appealing to the largest amount of people, which would obviously allow them to maximize their profit.

To be clear, I’m not saying popular art = the best art. I’m saying popular art = the most profitable art.

This is a sad admission to have to internalize, especially because most artists I know don’t think of themselves as production workers, and they don’t think of their art as a product or commodity. Art is more than that to them. Much, much more. And this, this idea that real art is not done for money but for the sole passion of creating and sharing it freely for the good of the common, is my last take away from the McLuhan quote above. My mind recalls Kester Brewin’s great book on pirates, Mutiny, in which I learned that Ben Franklin, of all people, was a heavy advocate for the common good. So much so that Comrade Franklin notoriously ignored British copyright laws and helped start libraries in the U.S. through what was essentially copyright piracy. According to Brewin, Franklin would also literally give his inventions away knowing that no creative person existed in a vacuum, that we are all influenced by, and build upon, what came before us. In Mutiny Brewin writes this:

“It is this attitude, the breaking down of enclosures that other nations had put up, the ability to synthesize and build on what others had done, that made America great in the first instance.”

This is an anarchic impulse that I resonate very strongly with, and I’m not alone (tangentially related here, I got a kick out of the following quote from critic Steven Heller describing Fiore’s design work being “as anarchic as possible while still working within the constraints of bookmaking”). Before Ben Franklin set foot in North America Native people in this land built complex, non-hierarchical societies that undeniably influenced colonial Europeans. And the more I learn about these indigenous egalitarian societies that lived on the land that I now call home the more I’m increasingly convinced (as are David Graber and David Wengrow) that Native Americans valued freedom in a way that baffled hierarchical Europeans back then and, honestly, still does today.

Tags:anarchismartcapitalismcopyrightDavid GraberDavid Wendgrowdesignindigenous philosophymarshall mcluhanmedia ecologyprivate propertyprocess philosophyprofitQuentin Fioreroland barthes

0 Comments