We Make Ourselves Real by Telling the Truth: Gun Violence and Tough Guys

“To be clear, toxic masculinity is not the demonization of all traits deemed quintessentially male or masculine.138 Rather, toxic masculinity is the combination of a few masculine traits taken to their extremes: at its base, toxic masculinity is predicated on dominance and control.139 It stands for the idea that gender constructs for men require them to “suppress[] emotions or mask[] distress,” “[m]aintain[] an appearance of hardness,” and use violence “as an indicator of power.”140 In other words, there is no room in society for men to express emotions typically perceived as vulnerable: sadness, fear, shame.141 And men that do are perceived as weaker and more feminine.142 It’s a worldview that both relies on and perpetuates insecurity and fear.143 To psychologists, Toxic Masculinity refers to “an extreme form of stoicism, dominance, violence, and aggression.”144 This is the 10,000-foot view. On the ground, toxic masculinity is a “constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia, and wanton violence.”145 Put differently, “it’s a manhood that views women and LGBT people as inferior, sees sex as an act not of affection but domination, and which valorizes violence as the way to prove [oneself] to the world.”146 Toxic, indeed.” – Hayley Lawrence, JD/LL.M.

“To be clear, toxic masculinity is not the demonization of all traits deemed quintessentially male or masculine.138 Rather, toxic masculinity is the combination of a few masculine traits taken to their extremes: at its base, toxic masculinity is predicated on dominance and control.139 It stands for the idea that gender constructs for men require them to “suppress[] emotions or mask[] distress,” “[m]aintain[] an appearance of hardness,” and use violence “as an indicator of power.”140 In other words, there is no room in society for men to express emotions typically perceived as vulnerable: sadness, fear, shame.141 And men that do are perceived as weaker and more feminine.142 It’s a worldview that both relies on and perpetuates insecurity and fear.143 To psychologists, Toxic Masculinity refers to “an extreme form of stoicism, dominance, violence, and aggression.”144 This is the 10,000-foot view. On the ground, toxic masculinity is a “constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia, and wanton violence.”145 Put differently, “it’s a manhood that views women and LGBT people as inferior, sees sex as an act not of affection but domination, and which valorizes violence as the way to prove [oneself] to the world.”146 Toxic, indeed.” – Hayley Lawrence, JD/LL.M.

The above passage comes from a research paper on toxic masculinity and gender based gun violence in America by legal scholar, Hayley Lawrence, that was written for the Journal of Gender, Race & Justice. I read it recently in the wake of yet another mass shooting in the United States (we’ve surpassed 200 so far in 2022), this one sadly claiming the lives of 19 children and two adults at a school in Uvalde, Texas. I’m left grasping for words and thoughts to express my grief and anger. I’m finding myself feeling despondent and disheartened as it appears that, once again, attitudes about guns and gun restrictions will not change, and a bleak sense of hopelessness blankets me as I sit and wonder how an incident like this doesn’t make everyone just immediately lay down their guns and turn into non-violent monks.

Although I’m fully aware that gun violence is actually connected with other types of violence like the violence of poverty, white supremacy, the carceral state, patriarchy, and class hierarchy I am left with this question:

Why do men like guns so much?

It’s a simple question and I’m sure many different men would have many different responses to this question so all I can do is speculate, but based on my observations over the course of my life, and my own experiences, toxic masculinity seems to be an inescapable factor at play in these shootings (and make no mistake, it’s men committing these massacres), and in fact it’s hard for me to believe that the impulses behind owning a gun for “self-defense” cannot just be boiled down to an insatiable desire to capture and maintain some fleeting sense of power, superiority, inadequacy, and/or security. In other words, for me it’s completely obvious that men who own guns for “self-defense” purposes actually just feel weak, inferior, inadequate, afraid, and insecure. This was definitely the case for me.

Although I’ve always been physically small with delicate, feminine like features (multiple times in my life people have told me that I could pass as female if I grew my hair long ((when I had hair))), I wasn’t always a radical, anti-violent, Christian activist who opposed things like the death-penalty, and didn’t always think that we all should turn our guns into garden tools. For a long time I denied my sensitive artsy nature and instead allowed myself to foster high levels of vindictiveness. If someone offended with me or disrespected me I believed it was my masculine duty to respond 10-fold. The idea of being thought of as weak or as a joke was simply unbearable to me. It’s undeniable that I valorized violence as a way to prove myself the world. Winding up in prison for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon was probably a natural outcome of this unexamined, inherited belief system (it contributed heavily at the very least ). I wanted to be a man and being a man meant that I needed to exhibit male traits, feign bravery, and command respect. My heroes growing up were muscle bound superheros who fought “bad guys.” I was primed to take part in the American myth of redemptive violence and believe me, I did. So I know about that of which I speak, and it doesn’t take a trained fucking psychologist to point out that this secondary emotion of angry vindictiveness was most likely a result of me feeling fundamentally weak, fragile, inferior, hopeless, insecure, inadequate, scared, and vulnerable but failing to (appropriately) acknowledge it and accept it.

I feel confident saying this though: holding a gun can make one feel pretty damn powerful. As Lawrence writes in the essay, “Owning a gun is an accessible and popular way of demonstrating one’s strength, independence, and self-reliance.”

I understand this. I do. I get it. As a scrawny kid who was picked on and body shamed (weighing 120 lbs. all through high school) I didn’t think twice when it came to carrying a weapon around. Guns are equalizers in a very real way. Lawrence again on this:

“At an even simpler level, guns are a source of maximal physical power. Even if one isn’t the strongest or most physically intimidating in the room, having a gun changes the power dynamic: it is an equalizer of sorts. That should make guns especially useful for women who are often perceived as the less physically dominant sex, and yet it is more often men that feel compelled to carry firearms. Firearms allow people, but men specifically, to demonstrate their toughness or inviolability with a mere glint of silver at the hip.”

I remember wanting very badly to feel like a tough guy, I wanted to feel courageous. So yeah, as a skinny girly-man who carried around a lot of anxiety and fear and who realized that I would never look like the hulking superheros I admired the only way I could be a “tough guy” and protect myself and the ones I cared about was to carry a weapon (Lawerence actually discusses this “Citizen-Protector” phenomenon in her paper). Or so I thought. It was my exposure to, and my deep investigation into the Christian faith while in prison (and shortly after leaving prison) that changed my trajectory. In particular, it was my encounter with the writings of Christian non-violent thinkers that impacted me the most. I distinctly remember reading Thomas Merton’s book New Seeds of Contemplation and learning that “We make ourselves real by telling the truth.” It struck me just how much I had been lying to myself, denying my true feelings of fear, vulnerability, insecurity, physical inadequacy, intellectual inferiority, etc. etc. etc. I could go on and on. To paraphrase Merton, I knew nothing of God. My life was centered on myself and I imagined that I could only find myself by asserting my own desires and ambitions and appetites in a struggle of competitiveness with the rest of the world. I tried to become real by imposing myself on other people, cutting myself off from other people in the process by building a barrier of contrast and distinction. I thought that I was all the more something because they were nothing. Thomas Merton taught me that the person who lives in division lives in death.

No person is an island. We need each other. It was when I was at my most vulnerable that I finally understood this. However, as Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing correctly observes, “It is unselfconscious privilege that allows us to fantasize—counter-factually—that we each survive alone.” Survival always involves others. Always. I noticed that as I began embracing the teachings of Christian anti-violence, learning to seek friendship and understanding in order to defeat injustice not people, the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. resonated with me in a way that was monumentally significant:

“Another of the major strengths of the nonviolent weapon is its strange power to transform and transmute the individuals who subordinate themselves to its disciplines, investing them with a cause that is larger than themselves. They become, for the first time, somebody, and they have, for the first time, the courage to be free.”

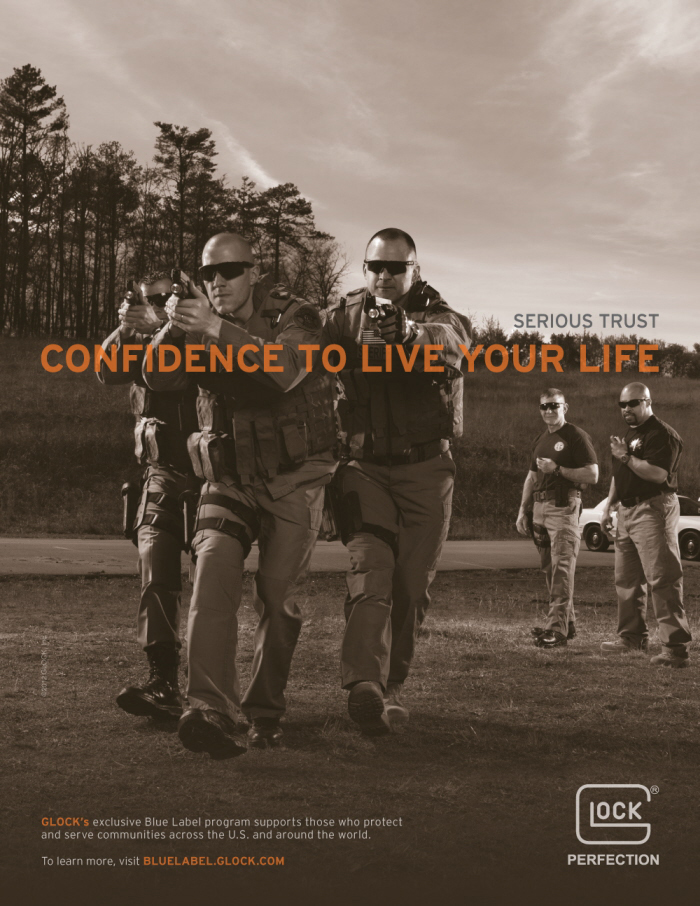

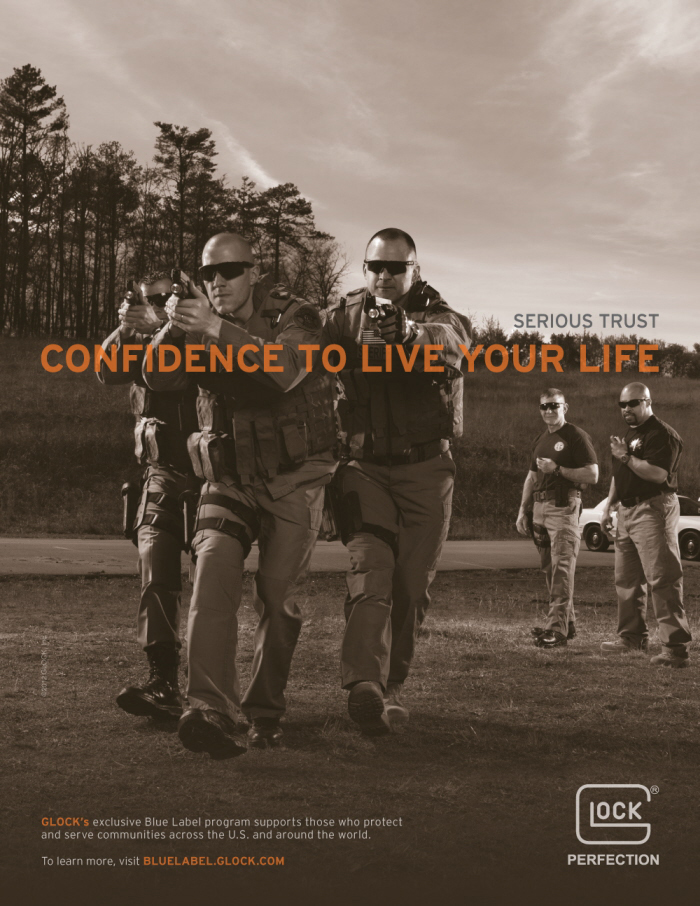

Contrary to the egregious gun ad above, I can’t think of a better symbol of instability and impervious distrust (in God and Human Nature, for instance) than that of a gun being carried on one’s person; it’s a dead giveaway (pardon the pun). But I also can’t pretend there are easy answers or solutions to gun violence because there aren’t any. As much as I wish guns would just disappear I know that won’t happen. I also know that men will continue carrying guns around and continue identifying with them because they’re seriously great for masking distress, suppressing emotions, and maintaining an appearance of hardness. But listen men, you’re not fooling anyone. Lets be honest, you’re not tough. You’re fragile, you’re vulnerable, you’re sad, you’re afraid, and you’re ashamed, just like me. As weak and counter-intuitive as this may sound that’s real and that’s where your confidence and your courage will be found. Praise be to God.

0 Comments