Search

Close

SpoOoOky Action at a Distance: Parapsychology, Occultism, Mechanistic Philosophy and How Miracles Became Super-Natural

At the center of the new philosophy of nature that emerged victorious in the 17th century was a mechanistic doctrine of nature. This position was, in fact, often referred to as the “new mechanical philosophy.” This view of nature had two fundamental dimensions, both of which exemplified the demand that all “occult” qualities and powers be banished from nature.

At the center of the new philosophy of nature that emerged victorious in the 17th century was a mechanistic doctrine of nature. This position was, in fact, often referred to as the “new mechanical philosophy.” This view of nature had two fundamental dimensions, both of which exemplified the demand that all “occult” qualities and powers be banished from nature.

…

One dimension was the elimination of all spontaneity, self-motion, or self-determination—especially any self-determination in terms of an ideal end (final causation)—from nature, which resulted in determinism. The second meaning of mechanism was that there can be no action at a distance: All causal influence must be by contact.

…

One of the factors making action at a distance such an important issue at the time was the “witch-craze” of the 16th and 17th centuries, which some historians consider the major social problem of the time (Kors & Peters, 1972). The accusations of witchcraft presupposed the idea that the human mind could directly cause harm to other people and their possessions. The mechanistic philosophy of Descartes and Mersenne, by denying that any action at a distance can occur and, more particularly, by denying that the mind can exercise influence upon remote objects (Descartes’ philosophy made it difficult to understand how the mind could even influence its own body), undermined the world of thought in which the witch-craze flourished and helped bring about its demise (Easlea, 1980; Lenoble, 1943, pp. 18, 89-96; Trevor-Roper, 1969).

…

A second theological-social problem, probably equally important, involved the interpretation of “miracles.” Competing with both Aristotelianism and the mechanistic philosophy was a wild assortment of Neoplatonic, Hermetic, Cabalistic, and naturalistic philosophies that had spread northward from the Platonic Renaissance that began in Italy in the 15th century. Some of these were “magical” philosophies, which allowed action at a distance. They specifically allowed the human mind to exert and receive influence at a distance—for example, through “sympathy.” These philosophies implied, and some of their proponents explicitly argued, that the miracles of the New Testament (and, for Catholics, the ongoing Christian tradition) were purely natural effects, not different in kind from extraordinary events that have occurred in other traditions and not requiring any supernatural intervention. Defenders of Christianity saw these philosophies as posing a profound threat, because the appeal to miracles as the sign of God’s establishment of Christianity as the one true religion was the central element in Christian apologetics. Many believed, furthermore, given the close relation between the Christian Church and the state, that the stability of the whole social fabric rested on this point.

…

The mechanistic philosophy was seen by many as the best defense of this traditional Christian position against the naturalistic interpretation of miracles. For example, Father Marin Mersenne, who was—along with Descartes, and in ways more important than Descartes—the central figure in the establishment of the mechanistic philosophy in scientific, philosophical, and theological circles in France, advocated the mechanistic philosophy on these grounds. Because it showed that no influence at a distance could occur naturally, the miracles that occurred in the New Testament and later Christian history were really miracles—that is, they required the supernatural intervention of God…

The above excerpts come from an essay by David Ray Griffin titled “Parapsychology and Philosophy: A Whiteheadian Postmodern Perspective.” It’s a great read.

…

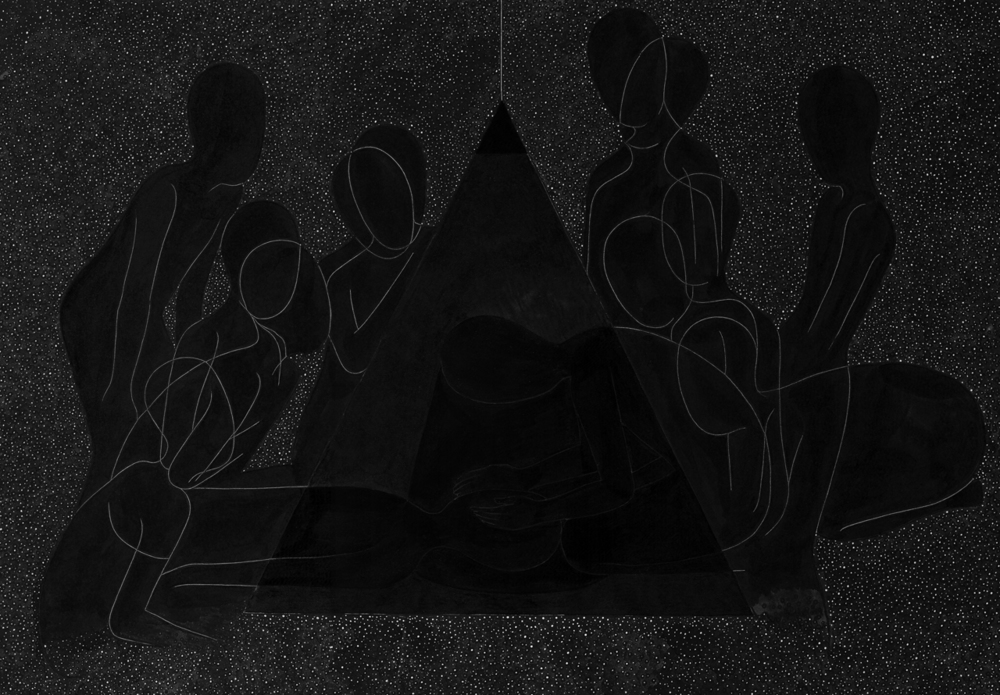

Drawing above by Moonassi

0 Comments