Accepting the World as It Is: Healthy Minds, Sick Souls, Radical Theology and Drugs

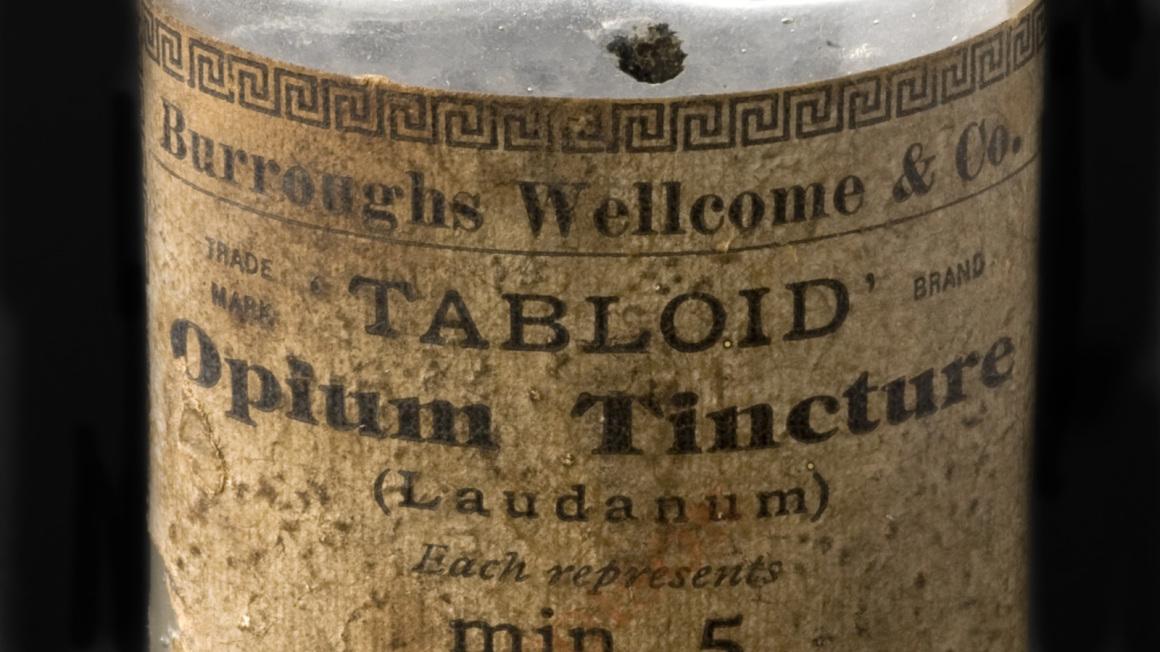

“Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.”

One of the big criticisms of religion that every serious spiritual/religious person has to grapple with at some point comes from one of the great masters of suspicion, Karl Marx (quoted above). I love Marx, and he and Freud have similar criticisms of religion. Both observe how religious belief can function as a crutch in peoples lives, a way to numb, delude and insulate ourselves from fully experiencing life in all it’s pleasure and pain.

Nietzsche is also one of the great thinkers who criticizes religion as being generally pernicious. Nietzsche famously declared the death of God, but as Daniel Barber has pointed out, Nietzsche’s proclamation has less to do with the death and decay of a metaphysical deity and more to do with the death of a certain human conception of God; namely, the all-powerful, transcendent God which is the organizing principle for the world. Nietzsche implored his readers to accept that gods die and then encouraged them participate in the becoming of the world.

As for Freud and Marx and their concern about religious beliefs potentially being used to enslave us by providing numbing sorts of illusory happiness, I think they’ve got a damn good point. But I also think William James makes a great point about religious experiences that needs to be considered, namely, there are varieties of them. For instance, we have “healthy-minded” folks on one end of the spectrum (think romantics like Emerson and Whitman plus various “theologians of hope”), and “sick souls” on the other (think Kierkegaard, Mother Teresa, Luther and Tolstoy). William James, in his book Varieties of Religious Experience, describes healthy-minded religious experience this way: “[W]e give the name of healthy-mindedness to the tendency which looks on all things and sees that they are good.” Richard Beck clarifies in his book The Authenticity of Faith that “The healthy-minded believer is positive and optimistic, willfully even intentionally so. The healthy-minded believer actively ignores or represses experiences that are morbid, dark or disturbing.” James thinks that when pushed to the extreme, healthy-minded religious optimism can become “quasi-pathological” producing “a kind of congenital anesthesia.”

Conversely, the sick soul can be described as a religious type of believer that tends to “maximize evil,” as opposed to ignoring it or sugar coating it. James describes the sick souls as being driven “by the persuasion that the evil aspects of our life are of its very essence, and that the world’s meaning most comes home to us when we lay them most to heart.” If healthy-minded folks use religious beliefs as anesthesia or to make themselves and those around them happy, sick souls use religious beliefs to “kill the party.”

So, Religious beliefs can certainly function pathologically, as Freud and Marx point out, but it seem that they can also function in healthy ways. The pragmatic response to the “religion as drug” or “religion as sugar coating” criticism might be to say ‘yes, religious beliefs can be used to numb out the pain of life, no doubt. But, like drugs, religions can also be effective in improving someones quality of life, and therefore can be truthful and valuable.’

The stream(s) of theology which emerged out of the death of God movement, loosely categorized under the name radical theology, heavily criticize transcendent forms of theology and, like Nietzsche, Freud and Marx, many of these theologians seem to heavily encourage all people to “accept the world as it is” and embrace a fully immanent worldview, which essentially means coming to terms with the contingency, uncertainty, and the rather bleak aspects of life (among other things); which is fine. But this demand always raises the rhetorical question in my mind: do these radical thinkers also encourage all people to give up their recreational drugs and prescription medications as well?

Again, pragmatically speaking, not everyone who uses drugs abuses them. Some people use drugs and alcohol for recreational purposes because they provide a nice break from their everyday “realities” or serve as a nice enhancement to them, i.e. drugs and alcohol make us feel good. Alternatively, some people take pain meds or psychological medication and find them extremely effective for improving their ailments (which might otherwise be debilitating) and therefore their quality of life. And actually (just going out on a limb here), might it be said that someone who chooses to take pain meds or psychiatric meds does so not because they are attempting to deny, negate, avoid or sugar coat any sort of “reality,” but precisely because they have already deeply felt the pain and suffering of “reality?” Maybe people use drugs because they already deeply know life sucks sometimes (which is what I actually think Marx is getting at above when he says “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering). Likewise, couldn’t it be said that a theology were one invests not in this life but in the life to come might be born out of an already deep acceptance of the painful immanent world we already live in, that we instinctively know and have experienced so vividly? Liberation theologian, James Cone on this:

“The Christian gospel is God’s message of liberation in an unredeemed and tortured world. As such, it is a transcendent reality that lifts our spirits to a world far removed from the suffering of this one. It is an eschatological vision, an experience of transfiguration, such as Jesus experienced at his Baptism…Bee Richards’s claims that “Jesus won’t fail you” was made in the heat of the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi, and such faith gave her strength and courage to fight for justice against overwhelming odds.”

Effective, true and very, very valuable. Cone says “Without concrete signs of divine presence in the lives of the poor, the gospel becomes simply an opiate; rather than liberating the powerless from humiliation and suffering…” William James would agree 100% with James Cone here.

Don’t get me wrong, I do think radical forms of theology are important and necessary tools. Some people could benefit tremendously from high doses of death of God theology (some people probably do need to do away with their pathological, transcendent, God-as-all-powerful-patriarch-in-the-sky religious beliefs altogether ((and I’d venture to say that many of these people look like me: white Euro-American men))). Others may only need a little bit or may not need it at all. Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., Oscar Romero and Desmond Tutu come to mind as four people who probably have/had transcendent views of God as their object of love, but lead tremendous lives filled with love, working tirelessly toward justice.

0 Comments