The Most Godly Thing God Can Do is to Become Human and to Die: Kester Brewin, Temporary Autonomous Zones, and AI

”In a broad sense, the Old Testament [sic] can be read as the story of empire, and the inevitable corrupting harms that royal, religious power does to people. In this schema, the New Testament is God’s denouement: the most godly thing God can do is to become human and to die. In the Mass, in the symbolic re-enactment of this mystery, this divine-body-become-human is broken up and shared amongst us. Meaning: it is only when we gather in community, it is only when we bring our bloody, messed up bodies together with all our hurts and hopes and differences and gather around this death of God, this invigorating absence of the Big Other — it’s only then that we approach the highest calling of our humanity: to love one another.”

The above passage comes from Kester Brewin’s remarkable book, God-like: a 500-year history of Artificial Intelligence in myths, machines, monsters which I recently finished and which I must say is fantastic! Brewin has been a favorite writer of mine for a while and his writing has just gotten better over the years. ‘God-like’ really does feel like the completed trilogy to my other two favorite Brewin books: Getting High: A Savage Journey to The Heart of The Dream of Flight, in which Brewin takes aim at the theological idea of transcendence by examining the human obsession with flight, and Mutiny! Why We Love Pirates and How They Can Save Us, a book about the cultural and social significance of pirates in which he frames them as symbols of resistance against oppressive systems.

In ‘God-like,’ Brewin, in his usual eloquent, reflective, interdisciplinary style of writing that is honestly very engaging, tackles the human desire for omniscience which, with only the slightest amount of thought applied, is revealed to be the rotten apple core that has given rise to Artificial Intelligence. Throughout the book, Brewin examines the deep historical roots of artificial intelligence, tracing its conceptual evolution over the past five centuries; he argues that our fascination with AI is not a recent phenomenon but is deeply intertwined with mythological, literary, and cultural narratives about being “God-like.” He explores how myths about gods, monsters, and automata reflect humanity’s enduring desire to transcend its limitations and achieve god-like powers, in this case limitless, god-like knowledge. Brewin’s thesis is that understanding these historical and cultural contexts is crucial for grappling with the ethical and existential challenges posed by modern AI technologies (and there are SO many of them!). But by recognizing the ancient stories that shape our current AI narratives, Brewin believes we can better address the profound implications of creating intelligent machines.

Perhaps my favorite part of the book is the last chapter titled “Human Autonomy in an Age of Automation.” It’s the longest chapter in the book but Brewin ties in his previous book, “Getting High,” by pointing out how when we enter into “higher states,” like the kind celebrated by various religions or the 60’s psychedelic-new-age subculture for example, we “abdicate ourselves from reason and enter into a flow, a state of ease where great wisdom is reveled. That or we tithe so that some priest will perform this role for us, vicar-iously.” Brewin’s concern with this is process is summed up nicely here:

”Though AI is a miracle of human engineering, its abilities with language and decision-making mean that we will soon be under great pressure to abdicate our executive functions to a Big Other again. Not a religious system as we might have traditionally understood it, but one that functions in the same way: promising us a path to augmentation and a means of remedying all our weaknesses but actually diminishing our human capacity for discretion and agency.” (pg. 165)

Brewin’s remedy for taking back discretion and agency is the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ), a concept originated by Hakim Bey but which Brewin wrote about (and which I first learned about) in Mutiny!. A TAZ. is basically a specific place where people can gather for a short time to perform together their intrinsic autonomy. A TAZ should be a place, according to Brewin, where “Real human contact should be the priority.” Brewin elaborates:

”In an era where digital fakery will erode trust, we need to give time to verifiable, physical interaction. In these spaces, we will practice our language arts and exercise the muscles of our executive functions. Discussion, debate, discretion, election, transparency, forgiveness, generosity. They will be places of gift exchange: a lift here, a meal cooked there, time offered to help clear a garden, coming together to help challenge an injustice. Sitting and eating together. It is only in this cycle of gift exchange…that our communal common-wealth will be enriched. Places not of commerce, and not where ‘free’ means ‘in exchange for all your personal data’, but places where liberty is experienced, where humanity is restored and sustained. Not places where we necessarily become more knowledgeable but where we become more known.”

Hold the standing ovation because Brewin isn’t done. These spaces where we encounter one another, these meso-level structures that we’re missing in our lives which could help with wresting back discretion and agency from AI and which may ultimately allow us to become more human (things like: choirs, sports teams, food banks, book clubs, theater companies, charities, or yes local churches) must have the death of god stamp:

”As they ate together, the collectives of the early church practiced the breaking of bread and the communal sharing of wine. In these symbolic foods, they were re-enacting the crucifixion of Christ, the symbolic disestablishment of the Big Other, the dethroning of this religious power structure that sustained an empire of oppression. In reality, this was no grand claim that the Roman empire was gone, that the Pharisaic forces of Temple Judaism had suddenly been overthrown. But for that time together they lived ‘as if’ that was the case, and in that temporary suspension of these power structures, new modes of being and new hints of resistance could occur.”

When I think of TAZ’s that I might have in my own life a few come to mind but one of them stands out: Valley Mosaic (VM), a group of friends that actually came together during the same time Kester Brewin was deeply involved in the Emergent Church movement and writing books about it. This small group, that originally came together to explore Christianity through creativity and the arts, has evolved into a very de-centralized, non-hierarchical religious learning, contemplation, and liturgical practice community where a different member of the group creates and guides the liturgy each Sunday evening. I don’t know what I’d do without the people in VM. Over the years it’s certainly been a group where I’ve encountered discussion, debate, discretion, election, transparency, forgiveness, and generosity, which Brewin indicates is so important, but it’s also been a place to express my creativity as well as a place to safely explore and question some of my most deeply held and unquestioned beliefs about religion, politics, economics, sexuality, violence, poverty, etc. Each week we teach each other something, eat and drink at the table of communion ever reminding ourselves that ‘we are what we eat,’ and do God’s work of looking our friends in the eye and asking how their weeks are going.

May we all establish temporary autonomous zones in our lives that allow us to flourish and be known. May they be places that allow us to bring our “bloody messed-up bodies together with all our hurts and hopes and differences” so that we can love one another and become more human in the midst of an in-human empire. Amen.

…

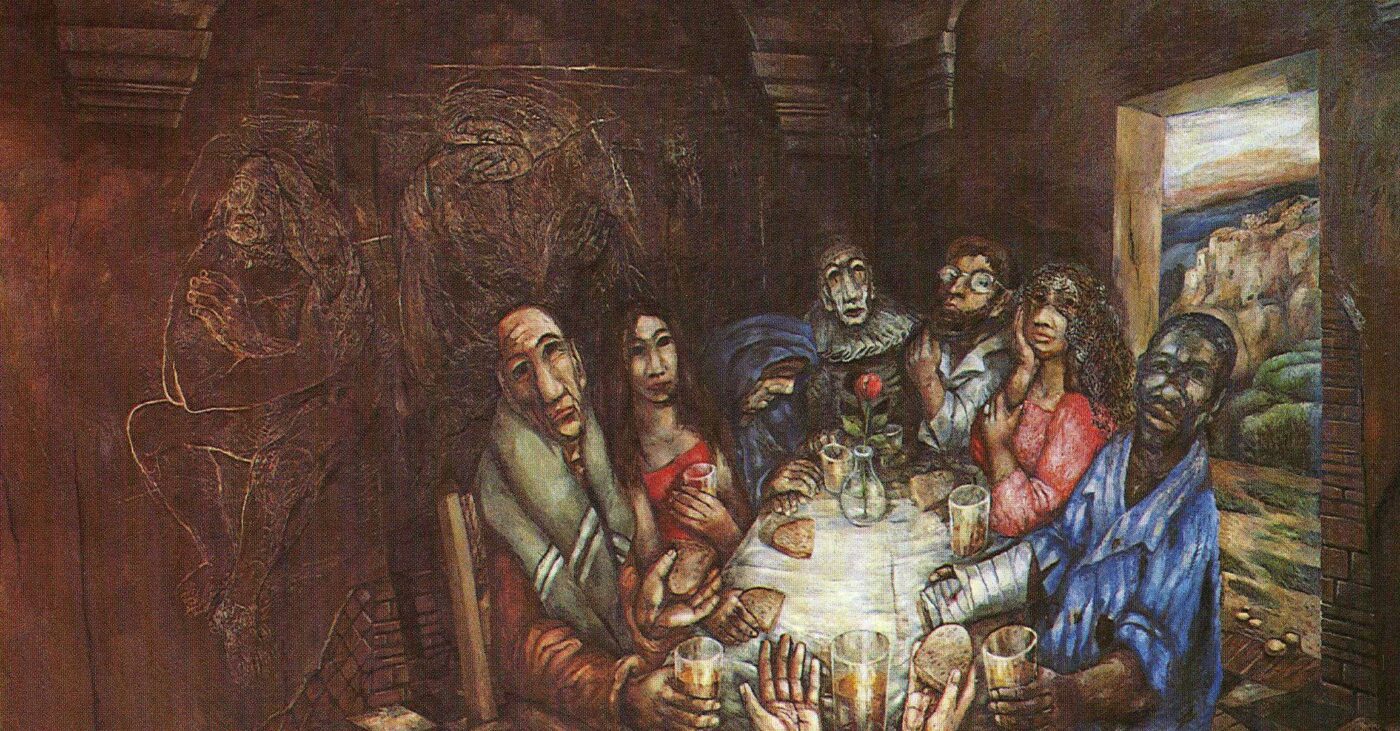

Painting above: “All Are Welcome” by Sieger Köder

0 Comments