Learning One’s Roles Well Is Like Learning One’s Native Language Well: Confucian Role Ethics

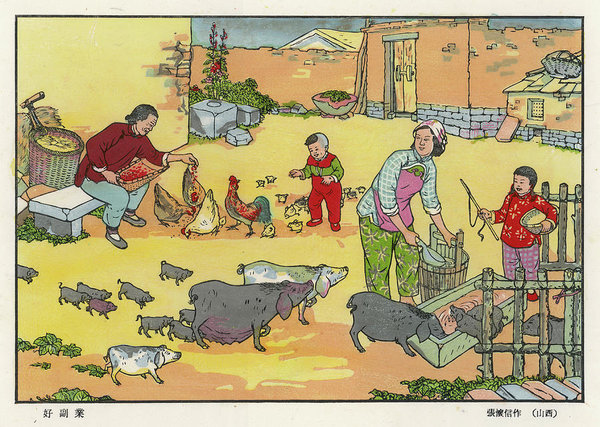

“Role interactions are mutually reinforcing when performed appropriately. The ideal Confucian society is basically family and communally oriented, with customs, traditions and rituals serving as the binding force of and between our many relationships and the responsibilities attendant on them. To understand this point fully we must construe the term li, translated as “ritual propriety,” not only for its redolence with religion, nor as only referring to ceremonies marking life’s milestones (weddings, birthdays, etc.) but equally as referring to the simple customs and courtesies given and received in greetings, sharing food, caring for the sick, leave-takings, and much more: to be fully social, Confucians must at all times be polite and mannerly in their interactions with others. And these interactions should be performed with both grace and joy. We are all taught to say “Thank you” – a small ritual – when we receive a gift or a kindness from someone. From the Confucian perspective, however, to say “Thank you” is also to give a gift, a small kindness, signaling to the other that they have made a difference, however slight, perhaps, in your life.

“Role interactions are mutually reinforcing when performed appropriately. The ideal Confucian society is basically family and communally oriented, with customs, traditions and rituals serving as the binding force of and between our many relationships and the responsibilities attendant on them. To understand this point fully we must construe the term li, translated as “ritual propriety,” not only for its redolence with religion, nor as only referring to ceremonies marking life’s milestones (weddings, birthdays, etc.) but equally as referring to the simple customs and courtesies given and received in greetings, sharing food, caring for the sick, leave-takings, and much more: to be fully social, Confucians must at all times be polite and mannerly in their interactions with others. And these interactions should be performed with both grace and joy. We are all taught to say “Thank you” – a small ritual – when we receive a gift or a kindness from someone. From the Confucian perspective, however, to say “Thank you” is also to give a gift, a small kindness, signaling to the other that they have made a difference, however slight, perhaps, in your life.

Roles are normative, guiding and constraining our behavior. But they do not confine. Teachers do not indoctrinate, friends do not betray friends, parents do not beat their children; but obviously there are many ways to be a good teacher, friend or parent, giving expression to our creativity. Consider an analogy with language: there are many ways to say “The boy threw the ball” (“The ball was thrown by the boy,” “What the boy threw was the ball,” “It was the ball that was thrown by the boy,” etc.). But “Threw the the boy ball,” is not among them. In just the same way that our creative use of language is only possible within the constraints imposed by the grammar, so too, living our roles creatively is guided, but not hindered by the definitions societies place on those roles.

The analogy goes farther: Learning one’s roles well is like learning one’s native language well in that the more one is exposed to others living their roles satisfyingly the more one will want to and can emulate them. In the same way, the more language we hear spoken, the more proficient we become at using it ourselves, and the more we experience others enjoying conversing with each other the more we will be inclined to enjoy conversation as well.

Taking the analogy still further, when language is used ungrammatically communication tends to break down, and when role norms are violated social interactions tend to break down. And just as grammar changes over time, repeated usage, and circumstances, so too, do roles change over time, repeated performances, and circumstances. Some grammatical sentences are more refined, charming, graceful or appropriate than others; so too, can role performances become more refined, charming, graceful and appropriate. If we take pleasure in particular turns of phrase we’ve uttered, we can take equal pleasure in the performance of our roles.”

The passages above are excerpts of Henry Rosemont Jr’s. book, Against Individualism: A Confucian Rethinking of the Foundations of Morality,Politics, The Family and Religion, that was published by Huff Post a few years ago.

Whenever I tell people I’m influenced by Confucian virtue and role ethics those unfamiliar or superficially familiar with Confucian philosophy tend to cringe because of the stereotypical rigid roles and compliancy they associate with the school of thought, not to mention the very real patriarchy that has troubled it (it’s sadly true that by neglecting to define the role of women, Confucius allowed those interpreting his texts to belittle and oppress women). However, I’ve found Confucian scholar Henry Rosemont Jr’s. updated rendering of Confucian thought to be most helpful for my 21st century Western ears and it fits perfectly with my process-relational philosophical and theological commitments.

0 Comments