Fallibility, Finitude, and Feeling Ashamed to Be Human

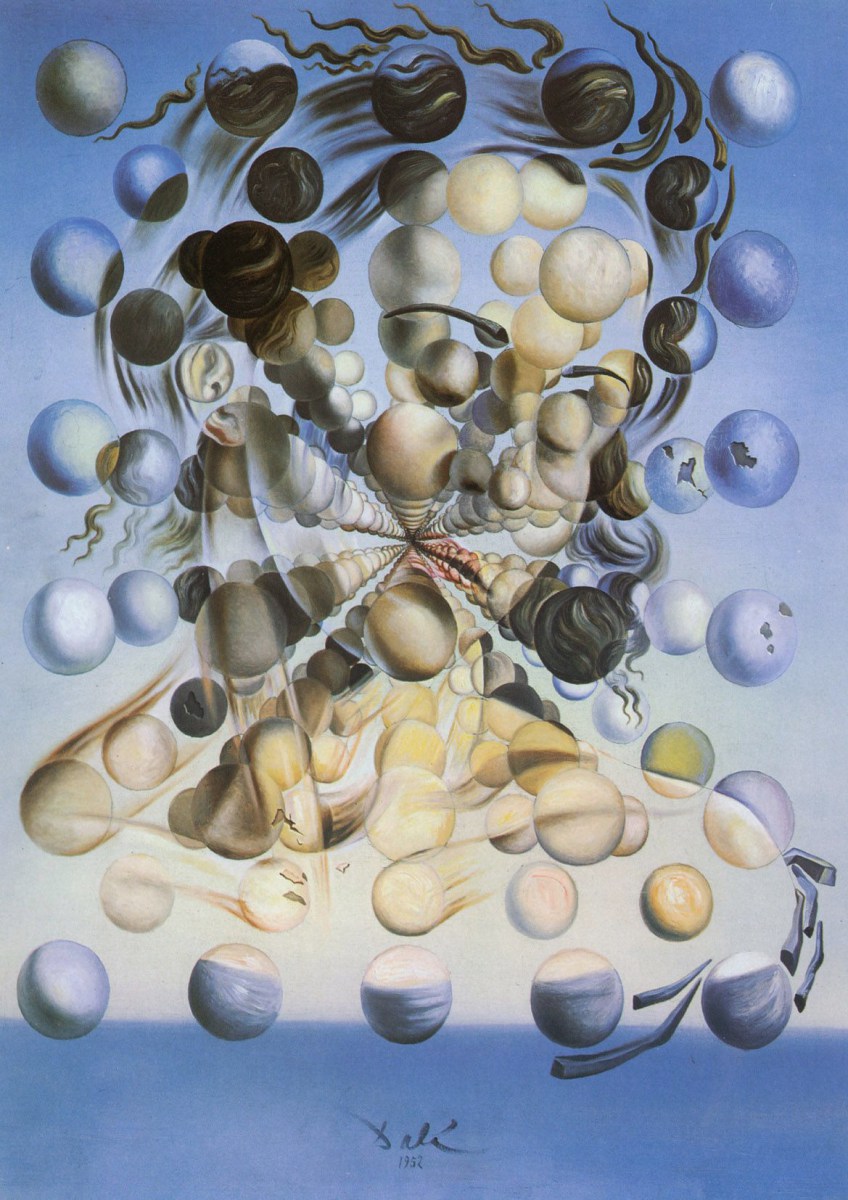

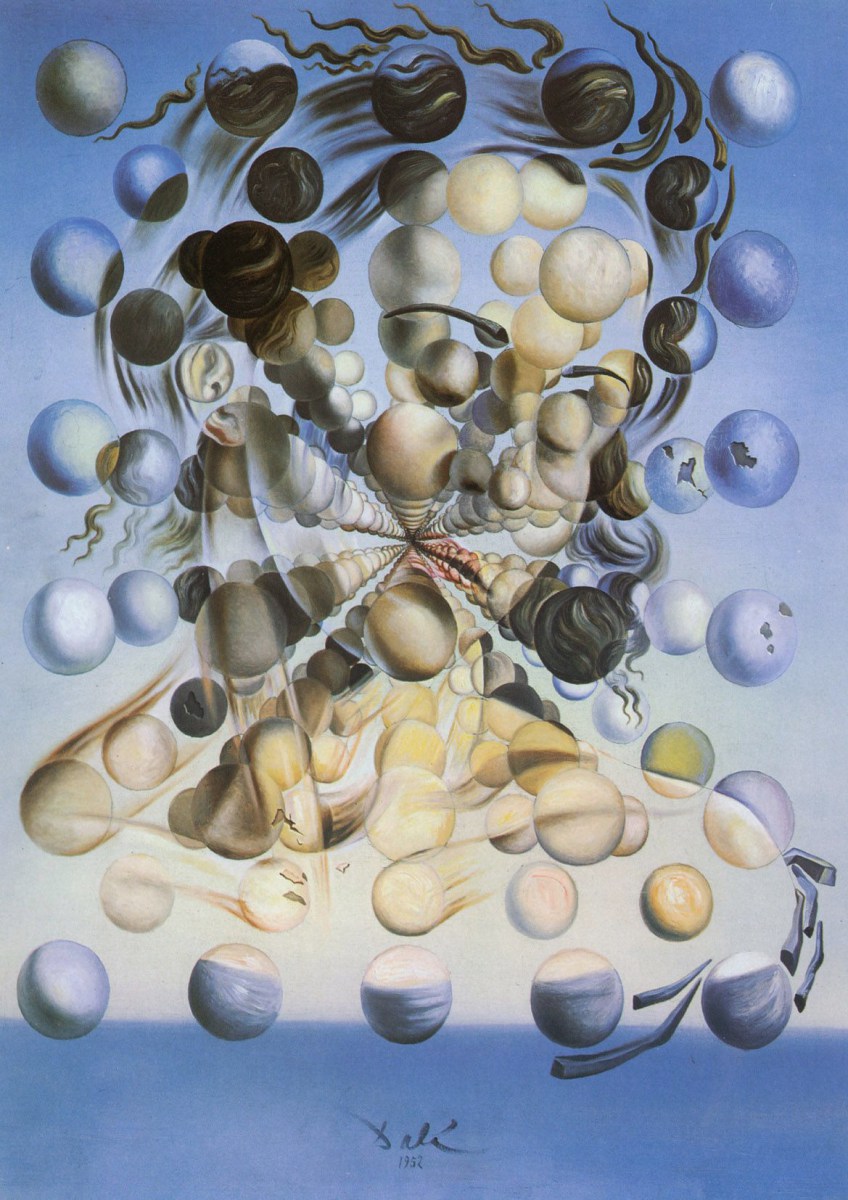

“Have no fear of perfection – you’ll never reach it.” – Salvador Dali

I know lots of people who have made relatively honest and minor mistakes at their workplace and have then been disciplined for it. These sort of scenarios always get me thinking about human nature and how, when we talk about mistakes, excellence, and human finitude and fallibility, we often tend to talk out of both sides of our mouth; on one hand there is an open recognition of how we can only do so much because, after all, we’re finite and no one is perfect, there is an expectation that mistakes will happen. But on the other hand there is a neurotic, meritocratic drive that looks down upon being “average” or “good enough” and compels humans to deny their fallible and finite nature in an effort to achieve some sort of pristine commodification.

It may seem that I’m being hyperbolic here but I don’t think I am. I’ve experienced this phenomenon myself and not just in the workplace; it’s definitely a cultural thing. Not long ago Megan Day wrote and article about the reality of “socially prescribed perfectionism” and discussed how neoliberal meritocracy creates a cutthroat environment that “places a strong need to strive, perform, and achieve at the center of modern life.”

But back to minor, honest mistakes. It seems to me that when presented with “a series of mistakes” or “continual oversight” as a reason for discipline the mistake-maker can legitimately respond with a paradoxical question: how many mistakes are too many? This question is paradoxical because it evokes the philosophical problem of vagueness; there is no clear, precise, universal way to tell how many mistakes equals incompetence. In other words, any criteria that is created to measure or gauge mistakes will be arbitrary and arrived at through vague affirmations/predicates. So, although we’re discussing minor honest mistakes here, even in a field like medicine, where a genuinely honest mistake made by a physician can have terrible consequences, the rules/guidelines/standards that are employed are still arbitrary in the sense that they were created by an authoritative ruling body (which consists of humans who are also fallible) and also relative since other cultures may indeed abide by other standards.

The point here is that humans make mistakes and, therefore, humans will necessarily make mistakes in the workplace. A person who makes honest mistakes (even a series of them in close proximity) doesn’t necessarily need “improvement,” in my opinion anyway (although sometimes development certainly is necessary)… Take the physician again for example: a brilliant surgeon who has saved countless lives throughout her career but has one bad day and makes a mistake that results in losing a patient, may indeed be forced to suffer the consequences of her severe mistake (perhaps she cannot practice medicine anymore ((I’m just speaking hypothetically here for the purposes of thought experimentation, I have no idea how the medical field actually deals with this stuff)). BUT, taking into account that physician’s track record, and remembering the countless people she may have saved throughout her career, I doubt many people would argue that one mistake is evidence enough that the physician needs to be labeled inept or incompetent or even viewed as mildly in need of improvement.

All of this, in a way, comes back around to observations that psychologist Richard Beck has made: that underneath our idolatrous push for excellence and/or perfection we may perhaps see the Freudian death drive in operation. Being perceived as “average” or “good enough” is often experienced by humans in our culture as a sort of failure, but, following Beck here, it’s less about failure and more about our human finitude. Being faced with our limits provokes existential anxiety and we’re reminded that we’re mortal and vulnerable to death. When we feel shame for being “average” or for “failing” (which I personally often do) we’re essentially feeling guilty/ashamed for being what we are: human.

…

Painting above: Salvador Dali

0 Comments