Every Seed Is Awakened: Why I’m Not Vegan or Vegetarian (Yet)

“If you are a feminist and are not a vegan, you are ignoring the exploitation of female nonhumans and the commodification of their reproductive processes, as well as the destruction of their relationship with their babies;

“If you are a feminist and are not a vegan, you are ignoring the exploitation of female nonhumans and the commodification of their reproductive processes, as well as the destruction of their relationship with their babies;

If you are an environmentalist and not a vegan, you are ignoring the undeniable fact that animal agriculture is an ecological disaster;

If you embrace nonviolence but are not a vegan, then words of nonviolence come out of your mouth as the products of torture and death go into it;

If you claim to love animals but you are eating them or products made from them, or otherwise consuming them, you see loving as consistent with harming that which you claim to love.

Stop trying to make excuses. There are no good ones to make. Go vegan.”

—Gary L. Francione

I recently attended a lecture with Gary Francioe (quoted above), law professor at Rutgers University and Animal Rights activist and abolitionist. Obviously, Francione is an outspoken Vegan and has lots of ethical arguments to back up why everyone else should be one too. Francione also calls himself an “animal abolitionist” because he makes a strong distinction between “animal welfare” and “animal rights.” Francione feels humans should stop fooling themselves by using the term “animal welfare” as if laws of this sort will stop exploitation of non-human animals (e.g. factory farming, abuse, poaching etc…). To this point, Francione makes clear that under anglo-american law, nonhuman animals are indeed considered legal property and economic commodities.

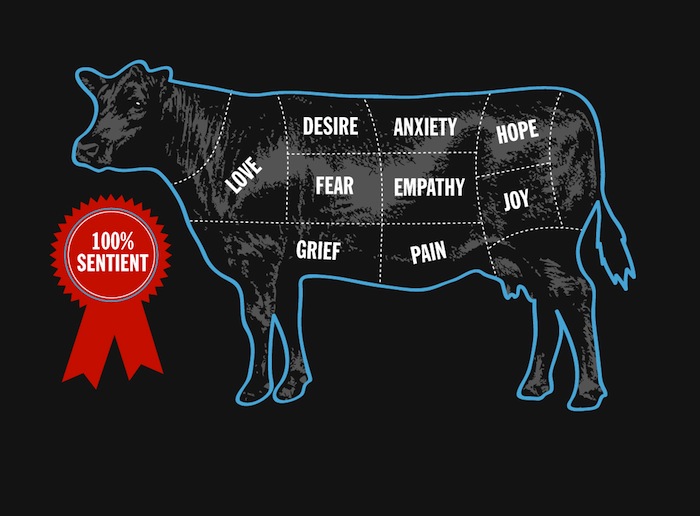

The part of Francione’s argument that is really persuasive to me as a process-relational thinker, was his emphasis that sentient non-human animals have interiority and self-awareness, and clearly exhibit an overwhelming interest in continuing to live and lead satisfying lives. This is made clear not only by the evidence of their sentience and emotional lives, but by the way that they struggle desperately to avoid death and remain alive, often even being willing to gnaw off their own limbs to escape from a trap.

Full disclosure at this point, I’m not a vegan or a vegetarian. I try adhere to the label of “selective omnivore” as closely as possible and might describe my self as attempting to keep a non-mammalion diet. But as a non-violent/anti-violent, process-relational oriented Christian, who recognizes that experience may indeed go the way down, and also as one who sees something convincing in Biblical arguments for vegetarianism/veganism, if something was going to push me into seriously considering a radical vegan lifestyle, it would be something like Francione’s ethical argument.

So Why Not?

Maybe it is so that those who argue for veganism or vegetarianism from the Bible are right, that we were vegan to begin with, and we will once again be so in the (here but still to come) messianic age. And maybe animal rights activists, like Francione, are correct when they argue that the animal rights movement is the logical progression of the peace movement, which will seek to end the treatment of animals as ends in themselves.

Now I’m the first to admit that I’m idealistic, but I do have to draw the line somewhere. And as much as I am tempted to embrace Francione’s radical biological egalitarianism, there are a couple things that prevent me.

1) Life is Robbery

Like Adam Kotsko has written in the past, I too have a distrust of very abstract totalising moral platitudes. Although I do claim to be non-violent/anti-violent in regard to humans (which is abstract and totalising enough), I really do think it is impossible to live and not and not kill anything at all or to live and not cause suffering to some sort of life-form. Whitehead might be right when he says “Whether or no it be for the general good, life is robbery.”

The idea that one does not have to kill to eat, I think, is simply naive. I tend to agree with ecologists when they say it is wrong to think of things in terms of a “food chain,” with humans at the top. Rather, a web or cycle may be more accurate. That is to say, from an evolutionary, synthesis-oriented perspective, we are all eating each other all of the time. For example, just in a tablespoon of soil one could find millions of organisms, along with urine, feces, blood and bone that the soil “eats.”

The conclusion I have come to then, is not whether or not to kill but where to draw the line.

This is where integral theory tends to help me, personally, and leads to the second reason why I’m not vegan (yet).

2) Development Has Never Gone Away

Just like most post-modern folks, I have a severe allergy when it comes to hierarchy. But no matter how hard I try I can’t get past the notion that disciplines like developmental studies exist and things like “altitude” or levels or stages of development seem to be real things in nature. As Ken Wilber points out, “that an acorn gets to be an oak by developing or growing somehow, and that, likewise, infants get to be adults by some sort of growth or maturation process” is really hard for me to ignore.

On top of this, add proposals like those put forth by process-relational thinkers such as Charles Birtch that “minds and bodies evolved together even though that body be only a proton or an atom” and it doesn’t take much to see why the utilitarian concept of “the greatest good for the greatest number” falls short. Wilber correctly, I think, points out that the famous Utilitarian slogan only addresses what he calls “span,” or the number of things contained on any given level (e.g. Grad School vs. Kindergarten – there are way more people in Kindergarten than Grad School), and leaves out what he calls the “depth dimension,” or the vertical levels contained in any thing (e.g. Complexity – think: a single cell organism vs. a human – humans would have more parts, more “depth” or complexity). If followed out logically then, “the greatest good for the greatest number” would allow for the greatest good to be done for something like viruses, since a billion HIV particles, for example, are produced everyday in an AIDS patient. Obviously it would be unethical to allow for this to happen.

The depth dimension shouldn’t be ignored. Instead of the greatest good for the greatest number, integral thinkers like Wilber advocate for the greatest depth for the greatest span. How this formula works out, though, is different for everyone. When Wilber talks ethics he brings up basic moral intuition (BMI), the idea that we all intuit the presence of spirit in the world and in each creature, and that we instinctively make decisions of depth all of the time when we make value judgements. So, as much as I put the ideal of love above all else, and as much as I am for updating arcane metaphysics which depict animals as unfeeling machines without interior emotional lives that can be exploited and treated as commodities, I don’t presently feel that this necessarily leads me to ethical vegansim (yet, anyway).

For me, when it comes to the general disuccion of whether or not to kill specific animals for food, the only thing I can think to do is ask myself the difficult question, ‘could I kill the animal myself?’ As much as I hate to admit it this is really just a way to measure and judge how much depth a sentient being has so that I can determine whether or not I am morally justified for committing a violent action; and we shouldn’t fool ourselves, we ALL do this. Obviously, some people draw the line at vegetables or shrimp; they feel they can stomach the harm they inflict on these sorts of life-forms (and make no mistake, plants do suffer when they’re killed). But, for those like me, who think they could muster up enough courage to kill a cow or a deer themselves, I pray to God that we do not take this killing lightly and that we are then lead to be thoughtful and consider all of the other factors involved in how our food comes to us (e.g. we should also be asking questions like, ‘did this creature live a decent life, or was it factory farmed?’ or ‘am I morally ok with how this non-human animal was killed?’). I hope that we would attempt to learn from the legendary environmental wisdom and spirituality of Native Americans like Sitting Bull, recognizing that “Every seed is awakened and so is all animal life. It is through this mysterious power that we too have our being and we therefore yield to our animal neighbors the same right as ourselves, to inhabit this land.”

…

An update to this post, a comment of mine from below:

My only real motive in pointing out that plants have feelings is to a) show how the utilitarian argument falls short, and b) to show how, as Dominque Lestel argues in his very good book, ethical veganism/vegitarianism can be very inconsistent, anthropocentric, and speciesist in some major ways. I think the ethical superiority of some types of veganism/vegitarianism comes through loud and clear and, in many cases (not all of course) only severs our connection to the natural world and reinforces an anthropocentric paradigm.

I tend to agree with Lestel, and other meat-eating indigenous cultures (e.g. Algonquin, North American) that seek to foster a cosmic kinship with non-human animals, that believe eating meat and other nonhuman animal products is actually a way to celebrate our relationship with the latter. In other words, we are to practice a “spiritual ecology” and it must entail an ethics of reciprocity between human and non-human animals whose terms can be fulfilled only through active and conscious participation in the cycles of generation and destruction that define life.

So with this ethical carnivorism in mind, I too am against things like factory farming, of course (which is what you’re talking about regarding usage of water and agricultural crops and deforestation, etc.). As Lestel writes, “Factory farming is a disgrace and the ethical carnivore can only agree with the political vegetarians’ assessment.” So yes, I agree with you that there are ways we can reduce the magnitude of our harm, and one of those ways is by being vegan. But there are other ways, and one of them is by being an ethical carnivore, who recognizes humanity’s sacred place in nature (not above it) alongside all the other sacred non-human entities. The implications of this naturalistic, panentheistic paradigm, I would argue, are also of great magnitude.

…

Graphic Above Found Here

I've had many Seventh Day Adventist friends who've I've argued with over the biblical implications of vegan life. Whether it's Biblically unclean meats or meat at all. We're reminded not to exploit our liberty to a person who's faith in Christ involves their diet (Not that you've done that in any way). You can't judge someone's frailty in faith. This comes from personal experience and is in no way a judgement on you about anything you've said.

I think you have missed one fundamental point: agreed - all life takes life, but vegans seek to avoid as far as possible the harm caused by their existence.

Your deal clincher was whether you could kill the animal. Most humans 'could' kill a cow - as every one of us has the capacity to murder another human, if not the wish to do so - but why do they want to? Life can be healthfully sustained on plant-based food. If you can live (very well, I'd argue) without killing a shrimp, hen, cow, etc, then why would you choose to do so, except to satisfy a rather selfish desire for the taste of animal products?

I enjoyed your article and would like to suggest that your future research includes watching, for example, the 'Cowspiracy' film (widely and freely available on the internet).

Thanks for reading, Helen, I appreciate your thoughts.

I respect that vegans do try to avoid causing as much harm as possible, and that’s great. I do too, in my own way as an aggressive peacemaker I guess. I admit that Francione may be right in that the animal rights movement is the logical progression of the peace movement…however I also do have to draw the line somewhere when it comes to abstract totalizing moral principles, like we all do. At this point, I’m fully aware that everything is eating everything all of the time. The linear way we currently view the food chain — the cow eats the grass, we eat the cow — is inaccurate. Instead, a cyclical view — the cow eats the grass, we eat the cow, the worms eat us, the grass eats the worms — is more accurate. In this sense, a person can’t be a vegetarian because even plants essentially eat animals.

I don’t rule out the possibility that I will someday be a vegetarian or a vegan; again, Francine’s arguments are seriously persuasive to me. Right now, however, I think a non-mamilian diet or a “selectivism” type diet is a way for me, personally, to do the most good.

Thanks again for reading!

So your argument hinges on two contentions:

1) Life is robbery.

This is true; however, a vegan diet requires just ~6% of the land, water, and energy needed by to sustain a meat eating diet. This is because the vast majority of agricultural crops go towards feeding livestock animals. Furthermore, animal agriculture is the single greatest contributor towards deforestation and greenhouse gas pollution.

Thus, even though we must rob the earth to live, we can reduce our harm by an order of magnitude by choosing vegan.

2) Plants have feelings too.

First, see point 1. A vegan diet requires only a tiny fraction of the plants needed for a meat eating diet. Secondly, a plant does not have a central nervous system, care for its young, or cry when it feels pain. Suppose you have a baby chick in one hand and a carrot in the other, and were asked to cut one in half. The choice is rather obvious to all non-psychopaths. This contention simply does not hold water.

Ken Wilber's foundational practice for development is "taking the role of other" in order to develop integral consciousness. This applies in our interactions with friends and family, while watching the news, while we buy goods, and while we eat. Try taking the role of other the next time you eat an animal, and see what happens when you really step into the life of that being. The inevitable consequence is veganism. Best of luck with your journey.

Hi Alex,

I appreciate the comment! Thanks for reading and engaging.

My only real motive in pointing out that plants have feelings is to a) show how the utilitarian argument falls short, and b) to show how, as Dominque Lestel argues in his very good book, ethical veganism/vegitarianism can be very inconsistent, anthropocentric, and speciesist in some major ways. I think the ethical superiority of some types of veganism/vegitarianism comes through loud and clear and, in many cases (not all of course) only severs our connection to the natural world and reinforces an anthropocentric paradigm.

I tend to agree with Lestel, and other meat-eating indigenous cultures (e.g. Algonquin, North American) that seek to foster a cosmic kinship with non-human animals, that believe eating meat and other nonhuman animal products is actually a way to celebrate our relationship with the latter. In other words, we are to practice a “spiritual ecology” and it must entail an ethics of reciprocity between human and non-human animals whose terms can be fulfilled only through active and conscious participation in the cycles of generation and destruction that define life.

So with this ethical carnivorism in mind, I too am against things like factory farming, of course (which is what you’re talking about regarding usage of water and agricultural crops and deforestation, etc.). As Lestel writes, “Factory farming is a disgrace and the ethical carnivore can only agree with the political vegetarians’ assessment.” So yes, I agree with you that there are ways we can reduce the magnitude of our harm, and one of those ways is by being vegan. But there are other ways, and one of them is by being an ethical carnivore, who recognizes humanity’s sacred place in nature (not above it) alongside all the other sacred non-human entities. The implications of this naturalistic, panentheistic paradigm, I would argue, are also of great magnitude.

Thanks again for engaging!

Plants are ALIVE thus important to eat. Animals are dead thus you are eating a dead corpse. I am shocked that Ken Wilber is not evolved enough to see the compassionate argument.

Well maybe that's just it as there is no 'argument. Animals have eyes, ears, brains, hearts, organs, etc, personalities and they enjoy their families. Animals can also suffer greatly by having

their legs then heads chopped off. I have worked in a slaughterhouse. I have seen first hand the horror in the eyes of a cow as she looked to me and other workers before she was skinned...

Yes. skinned. Many cows do not die from the shot. They have legs cut off and then are hoisted up by the neck to hang so the blood drains out. Is this humane?

is it humane to kill other beings so as to eat them? We do not need to eat or kill them as there is plenty of food plant based. Have a heart and look at this issue as it is rare that anyone

becomes a vegan by thinking about it or deciding from some fact. It's about kindness and compassion to cows, pigs, chickens, etc...

What is more important your taste buds or the life of another living being?

Why are people still putting animals in their mouth when there is plenty of quality nourishment without this animal abuse. To eat or drink anything that comes out of the butt of another being is

insane. :). The human brain will not decide the vegan path yet rather the heart as when you look in the eyes of one most vulnerable, the only pure decision is to let them live the life they have been ginve.

peace.

Just imagine 10 billion ethical carnivores. Then 20 billion. What does that look like. I think it looks a bit like going ourselves. Where are those pasture lands coming from?

Fooling ourselves*

I'm a radical left-liberal, compassionate egalitarian, and tree-hugging environmentalist who was raised in a new agey Christian church. I was vegetarian for a time. Also, I've known and lived with numerous vegetarians and vegans, including many family members (brothers, sister-in-laws, nieces, nephew, grandmother, aunt, and cousins).

Yet I'm now an carnivore. I go so far as to argue that a carnivore diet could be the most ethical and environmental-friendly diet, assuming it it is based on animal foods that are local, pasture-raised, and regeneratively farmed. If 'vegan' means causing the least harm, carnivore potentially could be vegan.

To understand my argument and to see the evidence, go to my Marmalade blog. Read two posts there: "Carnivore Is Vegan" and "Dietary Dictocrats of EAT-Lancet". Besides that, a carnivore diet is healthier for the body, particularly if it is nutrient-dense and nose-to-tail (organ meats, bone broth, butter, eggs, etc).