You can’t start with 1949 if you want to understand China: Martin Jacques and When China Rules the World

“Emmanuel Daniel (ED): Now, how would you apply your book, when you open the newspaper in the morning, and you read some of these issues coming out? What would you like to see China do? What would you like to see the West do? It shouldn’t be just capitulating that China owns the South China Sea. That’s not right. But at the same time, what needs to be the give and take in accommodating China?

“Emmanuel Daniel (ED): Now, how would you apply your book, when you open the newspaper in the morning, and you read some of these issues coming out? What would you like to see China do? What would you like to see the West do? It shouldn’t be just capitulating that China owns the South China Sea. That’s not right. But at the same time, what needs to be the give and take in accommodating China?

Martin Jacques (MJ): Well, that is a good question. So over time, the world needs to arrive at a modus vivendi with China, a way of living. Now, at the moment, you’ve got to look at the world, you can’t just say ‘the world’ because different parts of the world are responding in different ways. I see in the United States, and also for example, in my own country the UK, a regression. The United States has come to see China, starting with Trump, but of course, there’s a broad support for this position in America that China is a threat to its geopolitical position in the world. And as a result, there’s a kind of quiet fundamentalist rejection of China. Absolutely zero attempt to understand China. I mean, China became communist. It was like the Cold War again. It’s a denunciatory label, which has no understanding of what the Chinese phenomenon really is. You can’t start with 1949 if you want to understand China. You’ve got to understand Chinese civilisation over a much longer period. It seems to me that, once there’s some understanding of this, then relations can improve a lot. Because then you’re not fighting a zero-sum game, but you’re trying to understand China, just like China tries to understand the West. China has a much better understanding of the West than the West has of China. Because China is the new kid on the block in the present era. And it’s hard to make sense of America, understand the way America works. That doesn’t mean China has perfect knowledge, otherwise it would have seen Trump coming and it didn’t, basically. And this is not just for China, by the way, this is true for East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, Malaysia. They all have a much better understanding of the West than the West has of them. What we need is a process of a much greater and deeper mutual understanding of both what they have in common, of the affinities and also the differences. And what the West needs to do is really try and embrace a notion of what China is. Try and understand China in a different way. At the moment, you know, basically the position tends to be on our terms. And the international order, the rules-based system, oh, come on now, what do you mean by that? I mean, America has never observed the rules-based system anyway. It’s always been a privileged country because it basically kind of owned it or rather, governed the international system. The international system is in the process of being fundamentally renewed. Now that doesn’t mean that China’s going to boss the world. I don’t expect, quite frankly, for China to behave like the United States, because its history is very different. That’s not really the Chinese way. China’s much more keeping itself to itself in a way, whereas the Western tradition, because America gets it from Europe and then sort of accentuates it, is to run the world. Looking at it historically and contemporaneously, what the West is criticizing, in a way with China is a fear that China is going to be like the West has been. I don’t think that’s the case. Now it is certainly going to do things in its own way and we are going to have to get used to that because the Chinese are not going to become Western. They know a lot about the West, but they’re not going to become Western.”

The above transcribed quotes come from a recorded interview with British journalist, academic, and Marxist political commentator, Martin Jacques, in which he discusses a lot of ideas from his best selling book, When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order. I haven’t read Jacques’ book yet but I have read a lot of his essays and listened to a few of his lectures and I have determined that Jacques is most likely correct here (and apparently, since the first edition of his book was published in 2009, some other things he’s speculated about have come to pass as well).

I would particularly like to highlight here the part where Jaques points out how many in the West feel threatened by China because they expect China to become a European nation-state who, like European nation-states are known to do, go out and conquer/colonize other nations so they can “rule” them. Hey, colonizers are gonna colonize, right? Jacques, however, rightly implores his readers to glean a historical account of China in order to properly understand the culture. For example, his distinction about China being more of a “civilization state” versus a “nation state” goes a long way with regard to delineating some major differences. In an essay on his website, Jacques writes this:

“We choose to see China overwhelmingly in a context calibrated according to Western values: what overwhelmingly preoccupies us is the absence of a Western-style democracy, a lack of human rights, the plight of the Tibetans, and the country’s poor environmental record. No doubt you could add a few more to that list. I am not arguing that such issues do not matter – they do – but our insistence on judging China in our own terms diverts us from a far more important task: understanding China in its own terms. If we fail to do that then, quite simply, we will never understand it…For over two millennia, the Chinese thought of themselves as a civilization rather than a nation. The most fundamental defining features of China today, and which give the Chinese their sense of identity, emanate not from the last century when China has called itself a nation-state but from the previous two millennia when it can be best described as a civilization-state: the relationship between the state and society, a very distinctive notion of the family, ancestral worship, Confucian values, the network of personal relationships that we call guanxi, Chinese food and the traditions that surround it, and, of course, the Chinese language with its unusual relationship between the written and spoken form. The implications are profound: whereas national identity in Europe is overwhelmingly a product of the era of the nation-state – in the United States almost exclusively so – in China, on the contrary, the sense of identity has primarily been shaped by the country’s history as a civilization-state. Although China describes itself today as a nation-state, it remains essentially a civilization-state in terms of history, culture, identity and ways of thinking. China’s geological structure is that of a civilization-state; the nation-state accounts for little more than the top soil.”

Jacques’ words here are thoughtful and wise and while I read and listened to him speak about how important historical context is when attempting to understanding a culture a quote from Jenny Odell’s book came to mind: “Context is what happens when you hold your attention open for long enough; the longer you hold it, the more context appears.” I think Jacques is correct that if more people in the West (and in my context, the U.S.) focus their attention on studying the history of China and actually attempt to understand the culture on its own terms, versus simply ingesting political talking points from American liberal media who are obviously concerned with China doing to us what we have done to the rest of the World, we will all be better off.

…

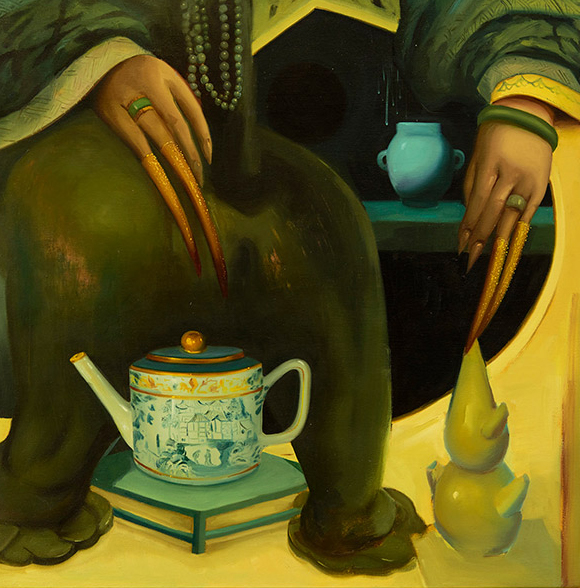

Art above by Dominique Fung

0 Comments