Pictures Are Worth a Thousand Feelings, I think: Media Ecology, Feelings, and the Decline of Abstract Rational Thought

“Regardless of what is being depicted in a photograph, the form itself evokes in us a particular pattern of intuitive, holistic thinking and emotion—the exact opposite of the pattern evoked by printed works. We have all heard the cliché “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Implied in this sentiment is the idea that images communicate information more efficiently than words. In some cases this is true, but the saying misses a greater truth. It assumes that one medium can function interchangeably with the other; thus, they are often put in competing positions. But in reality neither medium can accomplish what the other can. They are fundamentally different modes of discourse that create fundamentally different outcomes.

“Regardless of what is being depicted in a photograph, the form itself evokes in us a particular pattern of intuitive, holistic thinking and emotion—the exact opposite of the pattern evoked by printed works. We have all heard the cliché “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Implied in this sentiment is the idea that images communicate information more efficiently than words. In some cases this is true, but the saying misses a greater truth. It assumes that one medium can function interchangeably with the other; thus, they are often put in competing positions. But in reality neither medium can accomplish what the other can. They are fundamentally different modes of discourse that create fundamentally different outcomes.

It would be impossible for me to communicate the ideas contained in this book using only images—the form prohibits the content. At the same time, many aspects of our faith and life, such as profound grief or joy, are beyond words and are only given utterance through the imagery of painting, photography, video, or even dance […]

The image has a powerful ability to evoke strong empathy or sadness; it is a visceral and intuitive response. In contrast, the printed statement is an abstract proposition about an experience rather than a concrete presentation of an experience. Our brain processes each of these in very different ways. The printed word is processed primarily in the left hemisphere of the brain, which specializes in logic, sequence, and categories. In contrast, photographs and other imagery are processed primarily in the right hemisphere, which specializes in intuition and perceiving the gestalt—or everything at once […]

As image-based communication becomes the dominant symbol system in our culture, it not only changes the way we think but also determines what we think about. Images are not well-suited to articulate arguments, categories, or abstractions. They are far better suited for presenting impressions and concrete realities. Thanks to TV, political discourse in America is now based on intuition rather than reason. A presidential candidate is more likely to be elected if he/she appears likable, attractive, and trustworthy, all of which are subjective, intuitive evaluations based not on careful, left-brain analysis of a candidate’s policy positions but on the right-brain impressions of the mosaic television image.”

The above passages come from Shane Hipps’ 2006 book, The Hidden Power of Electronic Culture: How Media Shapes Faith, the Gospel, and Church, which I remember reading at the time of its publishing. I also remember being extremely excited to learn about media ecology and the works of thinkers like Marshal McLuhan and Neil Postman through this book; it’s definitely a good one! With regard to Hipps in particular, however, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that I am less than thrilled with his career trajectory which took him from being what, in my opinion, was a quite profoundly mystical Mennonite pastor to a “corporate leadership coach to Fortune 50 leaders.” SMH.

Anyway, I offer two connections here.

First, what brought Hipps’ book to my mind recently are two articles I read (here and here), which were both written by Professor Adam Kotsko, that deal with the inability of college students to be able to read effectively. Both articles are really worth reading (as well as Doctorow’s piece which is cited by Kotsko; PDF of that here). In his piece titled “The Information Environment: Toward a Deeper Enshittification Thesis,” Kotsko writes this:

“But beyond the asset-stripping enshittification Doctorow identifies, we need to acknowledge that there was another, broader enshittification of our relationship with information already implicit in the shift to the “information age.” A key canary in the coal mine for me here is Google Books…In short, Google Books assumes that what one wants out of their huge pile of books is not books, but isolated strings of information. That’s the same assumption that stands behind their disastrous attempt to revamp their search engine so that it doesn’t take you primarily to a website, but instead tries to directly present you with the answer. And arguably the culmination of that is ChatGPT, which promises to give you exactly the information you’re looking for in an unobtrusive “neutral” prose style. Much as I hate ChatGPT — and I do hate it with all my heart, unconditionally, unchangeably, eternally — I do get why that fantasy is attractive. But it is a fantasy, because as the man says, *there is nothing outside the text*. There is no such thing as the raw information devoid of presentation and context. We can’t get at that raw information, and we certainly can’t program computers to do so, because it does not exist. It is a fantasy, and it is increasingly a willful lie […] Our interaction with information has also been enshittified in more visceral ways. The internet may have given us access to the sum of human knowledge, but it gave it to us in an actively user-hostile form. Reading on the screen sucks. It actively injures our eyes. And there is no one alive who doesn’t realize that their screen reading is much less attentive and rigorous than their print reading. There are studies that show this, but I won’t insult your intelligence by linking them (if I could even find them on Google anyway). We all know it. Screen reading is inferior to print reading, even before we add in the distraction factor. We don’t remember what we read, and we have no tactile memory of where to find specific bits (“I know it’s on the lower left-hand page….”).”

Reading Kotsko’s article it seems very clear to me that one of the things we may also want to factor in here would be what Hipps (ala McLuhan and Postman) seems to have predicted: that image based communication mediums are, slowly but surely, eroding our ability to think categorically in abstract, rational terms and may inhibit us from being able to formulate and articulate complex arguments.

The other connection I’d like tease out here is one that I suspect may come off as a middle aged white guy griping about the language habits of younger people, but nonetheless I must persist lol! It’s this phenomenon of people saying ‘I feel’ in place of ‘I think.’ This phenomenon, to me, seems directly related to what is being discussed above with regard to how the communication mediums we shape also end up shaping us; i.e. it should be no surprise that people who are shaped by the image brought to us by the flickering pixels of our screens end up frequently blurting out things like this:

“I feel like John is cheating on me.”

I’m sorry but this is a thought not a feeling. There are NO feelings/emotions being presented in the statement above. All of the therapists I’ve talked to and read over the years have concurred that thoughts and feelings intermingle and give rise to each other, but we must present both when we attempt to communicate. For example, a range of emotions could be triggered from the thought, “I think John is cheating on me”:

Anger: “I feel angry because I think John is cheating on me.”

Fear: “I feel afraid because I think John is cheating on me.”

Happiness: “I feel happy because I think John is cheating on me.”

Sadness: “I feel sad because I think John is cheating on me.”

The one other thing to mention about this, which is important and should be kept in mind, is that thoughts, unlike emotions, can be challenged or verified empirically (i.e. there are multiple ways we can verify if John is cheating or not). By using “I feel” in place of “I think” we should be aware that one may be (unconsciously?) trying to short-circuit such empirical examination; at least this is the case for me because I certainly catch myself doing this too! If someone challenges my “feeling” about John cheating I can merely say ‘please don’t invalidate my feelings, asshole! Initially I started doing this because I thought it was funny and wanted to play along with everyone online. But seriously, at some point we all must understand that prefacing out thoughts with “I feel like” does not magically transform those thoughts into feelings. We are at best fooling ourselves, and at worst, being disingenuous with our conversation partners.

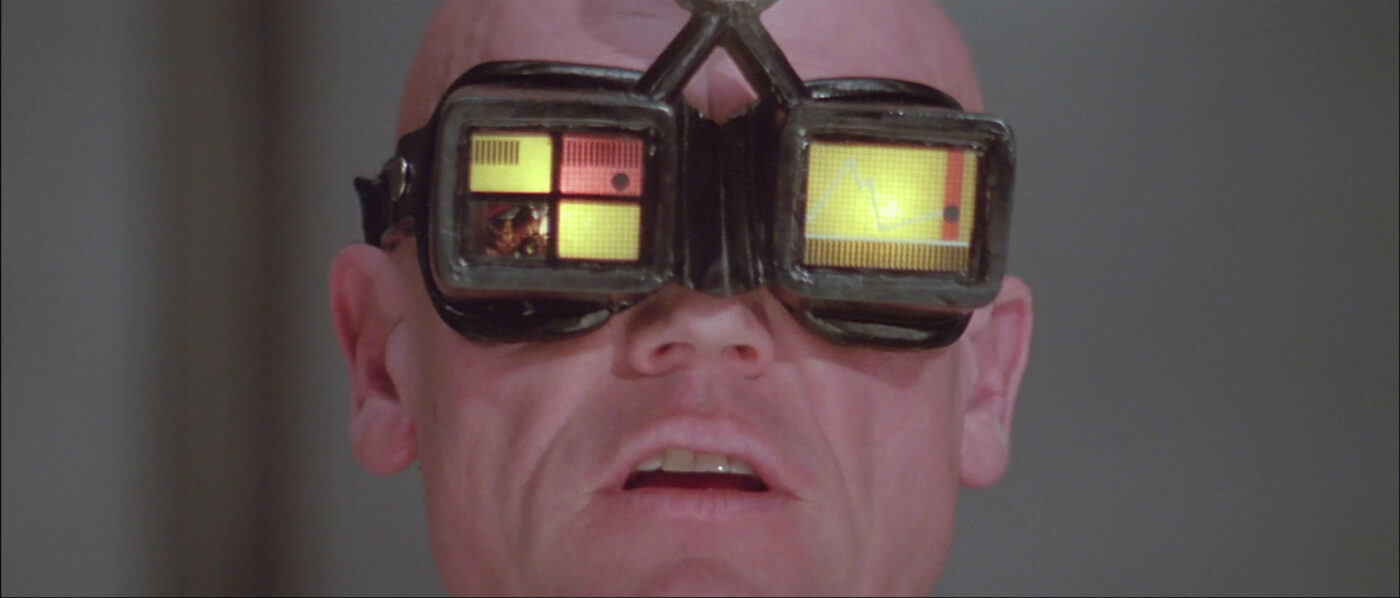

Now would balancing our screen time with paper books enable us to nurture the “left-brain” critical thinking and abstract reasoning abilities that are obviously eroding? Who knows, maybe. This has been my plan for a while and I suppose I’ll stick with it, at least until Ming the Merciless forces us to wear Apple Vision Pro goggles at all times (pictured above).

0 Comments