Atheism and Imagination: Re-imagine nature as in some way ensouled, or re-think the human soul as somehow mechanical

“One example of this mode of perception, or ‘prehension,’ is our awareness that our sensory organs are causing us to have certain experiences, as when we are aware that we are seeing a tree by means of our eyes. Such prehension, while presupposed in sensory perception, is itself non sensory.” —David Ray Griffin

“One example of this mode of perception, or ‘prehension,’ is our awareness that our sensory organs are causing us to have certain experiences, as when we are aware that we are seeing a tree by means of our eyes. Such prehension, while presupposed in sensory perception, is itself non sensory.” —David Ray Griffin

I made some comments on Tony Jones’ blog post a few weeks ago which was about atheism. I thought I made some pretty thoughtful comments during the dialogue in the comment section, but some people thought I was unfairly characterizing atheists and some seemed to be upset that I implied that fundamentalist atheists (as well as fundamentalist religious people) don’t use their imaginations when it comes to cosmology and philosophy. So, most of my comments are basically trying to clarify my first comment…HA!

I’m reposting my comments here in case I want to refer back to the conversation someday. I think they’re still pretty great to read without the other part of the conversation, but you can read all the comments on Tony’s post here.

…

Tony, your Carroll quote is pertinent in the Atheist/Theist discussion. Doubt is ok, but we can’t stop using our imaginations, which I feel a lot of atheism (and agnosticism) kind of does (I’m thinking of the rational, materialistic, empirical, scientistic type here).

I like when Matt Segall talks about Etheric Imagination not being “in the business of fantasy or make believe, but is an organ of genuine conceptual and perceptual import in tune with natural processes that unfold below the level of ordinary rational waking consciousness.”

To further quote Segall, and John Cobb, plus plug the 10th International Whitehead Conference at the same time:

“The discoveries of deep time and biological evolution that emerged during the course of the 18th and 19th centuries dealt the death blow to substance dualism, forcing humanity to make a fateful ontological decision: either, as Cobb puts it, (1) re-imagine nature as in some way ensouled, or (2) re-think the human soul as somehow mechanical. In the 20th century, Western techno-science committed itself to the second project: human society and the earth itself were to be re-made in the image of the machine (if ancient cosmologies suffered from anthropomorphism, modern cosmologies suffer from mechanomorphism). Our early 21st century world, with its exploding economic inequality and ecological unraveling, is the near ruin lying in the wake of that decision.”

Seems like most thinking atheists I know can definitely get on board with Cobb’s first choice there. Why wouldn’t one want to envision and believe in a world that is alive and indeed filled with the sacred?

…

Hi James, thanks for engaging. Didn’t mean to offend or anything. Again, I had a very specific type of fundamentalist atheist in mind when making my earlier comment.

In regard to your question though, it’s not that atheists or agnostics are not using their imaginations, I confess I overstated that. We all use our imaginations but unfortunately, our operating systems/worldviews/metaphysics/ideologies tend to limit our creative vision sometimes. Here is another quote from Segall’s write-up that gets to this point:

“The mechanical ontology underlying scientific materialism stems from misplaced concreteness, whereby abstract models of physical activity are made to fill in for the experienced reality of said activity. Such a scientific materialism, though it claims to be empirical, is really a confused idealism, in that it dismisses experiential reality as a mere dream, replacing it with an explanation based on the conjectured mechanical processes lying beneath experience that somehow cause it.”

Incidentally, I also happened upon this awesome quote today: “It is by logic that we prove, but by intuition that we discover. To know how to criticize is good, to know how to create is better.” ~Henri Poincaré

Peace ✌

…

James, btw, as far as understanding reality goes, you may be interested in Philosopher Catherine Elgin’s epistemological work. She is also a big fan of imagination and astutely points out that scientific experiments are “fictions,” or as she puts it “vehicles of exemplification. They do not purport to replicate what happens in the wild. Instead, they select, highlight, control and manipulate things so that features of interest are brought to the fore and their relevant characteristics and interactions made manifest…”

For Elgin, when it comes to ways of understanding reality, thought experiments can be just as useful (if not more so) as physical, scientific experiments performed in a lab. Further, for Elgin, works of fiction are, in many cases, thought experiments. Elgin again:

“Like literary fictions, thought experiments neither are nor purport to be physically realized. Nevertheless, they evidently enhance understanding of the phenomena they pertain to. If fictions are thought experiments, they advance understanding of the world in the same way that (other) thought experiments do.”

Rock on.

…

James, you make great points. And no doubt, man, I’m with you, hooray for science! HA! The modern, scientific, rationalist worldview has indeed brought us a long way.

You’re also right when you say scientists use their imaginations. My only issue is when folks who hold to a reductionistic mechanical type of imagined vision of reality/ontology (what Whitehead calls scientific materialism), think this in the only way (or even best way) to imagine reality.

I want science to the best it can be. I also want religion to be the best it can be. In order to do this, both ways to explore reality need to be able to be able to practice what Keats called “Negative Capability,” which is the power or potency of the human imagination to think without acting, i.e., to contemplate the possibility of something without assuming its actuality.

For instance, when fundamentalist atheists like PZ Myers ridicule the notion of “spiritual exercises” for atheists, it illustrates well the conceptual blockage preventing scientific materialists from considering anything other than deterministic mechanical laws in their explanations of the natural world.

Likewise, when religious fundamentalists dismiss evolution, and fear science, it shows a stunning lack of theological imagination which prevents them from giving up the harmful and idolatrous image of god they’ve held onto for so long with such pathological certainty.

Again, we’re on the same team here. Let’s imagine a better world ✌.

…

Whoa. Take it easy man. I’m not railing against anything, accept maybe a particular type of eliminative, reductionist, fundamentalist worldview.

To put it simply: I’m criticizing an ideology here (we all have ’em, they can blind us or open our eyes), not necessarily a methodology (the scientific method is a great way to investigate reality). I criticize the same type fundamentalist ideologies in religion.

Also, spend some time reading Elgin before you criticize her. Her colleagues at Harvard think she’s pretty great. Her epistemology can be summed up thusly: she considers the pursuit of understanding to be of higher value than the pursuit of knowledge. For Elgin, art, like science, embodies, conveys and advances understanding.

We’re all on the same team here, man. We’re all just trying to understand.

…

Hi Steve,

To copy and paste from a comment I made above:

I want science to the best it can be. I also want religion to be the best it can be. In order to do this, both ways to explore reality need to be able to be able to practice what Keats called “Negative Capability,” which is the power or potency of the human imagination to think without acting, i.e., to contemplate the possibility of something without assuming its actuality.

For instance, when fundamentalist atheists like PZ Myers (and his many many followers) ridicule the notion of “spiritual exercises” for atheists, it illustrates well the conceptual blockage preventing scientific materialists from considering anything other than deterministic mechanical laws in their explanations of the natural world.

Likewise, when religious fundamentalists dismiss evolution, and fear science, it shows a stunning lack of theological imagination which prevents them from giving up the harmful and idolatrous image of god they’ve held onto for so long with such pathological certainty.

Peace ✌

…

Yeah I guess I am missing your point because I’m simply not on board with anything that feels like eliminative-techno-scientific-reason-all-the-way-materialism or dualistic-fundamentalist-religiously-unthinking-idealism. That’s all.

When I say we need to use our imaginations I’m talking about examining our world views and operating systems/metaphysics, and imaginingg that there may be better ones out there, and if not then we should imagine some new ones. Someone who makes the statement, “If there is any other way than of knowing reality but through empirical evidence, I’d love to know what could be” obviously has a worldview and a metaphysic, and it’s most likely closer to the eliminative-techno-scientific-reason-all-the-way-materialist option.

The eliminative-techno-scientific-reason-all-the-way-materialist worldview collapses the subjective into the objective, i.e. for materialists, the subjective just happened to pop-out of the objective one day. That’s what reductionistic materialism is and that is one place where this blockage of imagination I’ve been talking about lies.

Now if I were going to pick one side or the other, I’d pick the eliminative-techno-scientific-reason-all-the-way-materialist side over the dualistic-fundamentalist-religiously-unthinking-idealist side, but what keeps me from doing that is Kant’s transcendental position. To quote Segall again, “what so many scientific materialists seem to neglect is that a reduction of human consciousness to the deterministic playing out of neurophysiological mechanisms is also a reduction of the scientific enterprise to a talking primate’s delusion of grandeur. If consciousness (and with it, rigorous logic and honest empiricism) is just an empty word, just a culturally acquired illusion with no causal or physical role to play, then we have no reason to take science–one of human consciousness’ greatest achievements (right up there with art, religion, and morality)–seriously. Neuroscientific reductionism (usually unknowingly) undermines its own philosophical conditions of possibility. As Hegel argued, it treats spirit as though it were a bone.”

You ask about other ways to investigate reality, Steve. There are many (see what I wrote about Catherine Elgin in my comments above), but from a process-relational prospective, which puts forth the proposal that the objective and subjective have existed as long as anything has existed (http://turri.me/?p=116), then art, philosophy, science and religion are all fantastic ways to explore and gain understanding of reality.

Thanks for engaging, man.

Rock on

…

Steve,

You’re a smart guy, man, and I love these kind of dialogues because it forces me to think through what I think I know 🙂

First, you keep using the term “caricature” but I prefer “generalization.” We all make them all of the time, all statements of fact or truth require generalizations. To paraphrase Adam Kotsko, so you know two or three people in a particular group who don’t fit a generalization? Who cares? The point of a generalization is to say what is true most of the time — the usefulness of a generalization lies precisely in the fact that it allows us to ignore the exceptions for the purpose of discussion. When people forget that there are exceptions, yeah, that’s bad, but it’s worse when people make discussion impossible by accusing everyone who makes a generalization of thinking that the generalization is unconditionally true in every case. Of course I know that not all atheists are “fundamentalists” just like all religious people are not “fundamentalists.”

When I use the phrase “fundamentalist atheist” I’m referring to a particular group of folks who don’t like religion, who would want to see it eradicated from the Earth, and who also conflate atheism with skepticism and critical thinking (read more here). These same people also tend to hold to an eliminative, reductionistic view of the world and the human mind and who also hold up scientific empiricism as the end all be all of human understanding. I know people like this. Sometimes the label “New Atheist” is applied to these sorts of folks.

Second, the generalization I make by using the goofy term “eliminative-techno-scientific-reason-all-the-way-materialist worldview” I think is an accurate one as it really does describe how some people view the world. For a lot of the folks, like the ones I described above, consciousness/subjectivity is simply reduced to an epiphenomenon, completely dependent on physical functions. This is what I mean when I say the subjective is collapsed into the objective in a monist materialist ontology.

Third, you keep asking how we can know reality apart from empiricism. I’ll start by saying that I currently hold to a process ontology, not materialism, not idealism. Empiricism, as a theory of knowledge that emphasizes the role of experience, especially sensory perception, is great! But if one is intellectually honest, one must take the Radical Empiricist critique of Whitehead and Williams James seriously.

Whitehead (and James), to quote David Ray Griffin extensively, deconstructs “sensory perception showing it to be a hybrid of two pure modes of perception. Hume and most subsequent philosophy noticed only ‘perception in the mode of presentational immediacy,’ in which sense data are immediately present to the mind. If this were our only mode of perception, we would indeed be doomed to solipsism of the present moment. But this mode of perception…is derivative from a more fundamental mode, ‘perception in the mode of causal efficacy.’ In this more fundamental mode, we directly perceive other actualities as exerting causal efficacy upon us—which explains why we know that other actualities exist and that causation is more than Humean constant conjunction. One example of this mode of perception, or ‘prehension,’ is our awareness that our sensory organs are causing us to have certain experiences, as when we are aware that we are seeing a tree by means of our eyes. Such prehension, while presupposed in sensory perception, is itself non sensory. In seeing a tree, I do not see my brains cells or my eyes, but I do prehend them and hence the data they convey…Another example of this non sensory perception is our prehension of immediately prior moments of our own experience, through which we know the reality of the past and thereby of time.”

The concern here, to put it way too simply, is that there is way too much focus on analysis at the expense of the bigger picture: connections, causality, meaning. Both elements are equally present in experience and both need to be accounted for.

If you’re interested in learning more about this different and imaginative way of thinking, let me know man. I’m happy to chat with you privately.

Peace out ✌

…

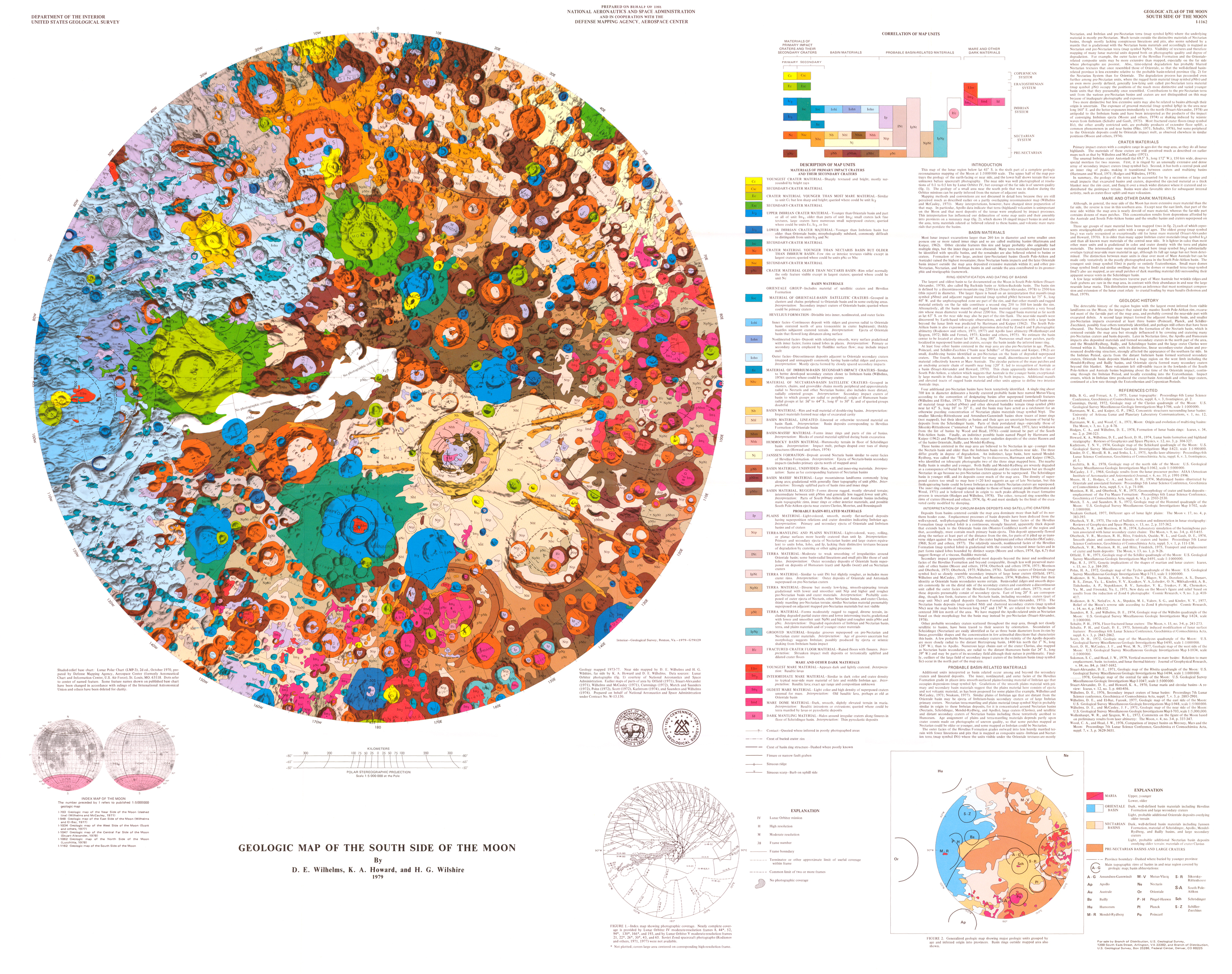

Image above: Geologic Atlas of the Moon

0 Comments